Actual Budget for YNAB users

This is an explanation of Actual Budget for YNAB users. With YNAB's recent price increases, I decided now would be a good time to see how the alternatives are fairing. I was really surprised with how competitive Actual was! It has some features that I think would be great for YNAB to adopt, and a few shortcomings (though nothing major).

This was exciting to me for a few reasons. First, Actual is open source. I'll never have to pay for it, and I can help out if I want to. Second, Actual is fast, quite faster than YNAB in my experience. It loads quickly on mobile and much faster on desktop. And third, Actual has a lot of features that YNAB doesn't have. While YNAB users love to talk about the features that are missing from YNAB alternatives, I was delighted to find a relatively feature-complete YNAB alternative that actually has some things I wish YNAB had.

This post is a guide to using Actual for heavy YNAB users. I'll show you how to set it up, import your budget, and what all of the equivalent things in Actual are (compared to YNAB). Without further ado, let's get started!

Setting up Actual

There's a few ways to set up Actual to use it.

If you are nontechnical (read: if you don't know what the words Docker or Node.js mean), use PikaPods. This is a service that you pay a flat monthly fee to host Actual for you (as low as a dollar a month!). Setting up should be pretty easy, and you get $5 for free!

If you're technical, you have a few choices. You can install Actual locally on your laptop with Node.js. Or if you have a NAS or a server, you can install it with Docker. Note that wherever you install it, you will need SSL in front of it. You cannot serve Actual just off of an http endpoint, it has to be https. Otherwise certain browser features that Actual uses will not be enabled. I use Cloudflare's zero trust tunnel and it works fantastically for me.

Once you get Actual running, set it up with a password (pick something you'll remember). Then you'll want to import your YNAB budget.

Importing a budget from YNAB

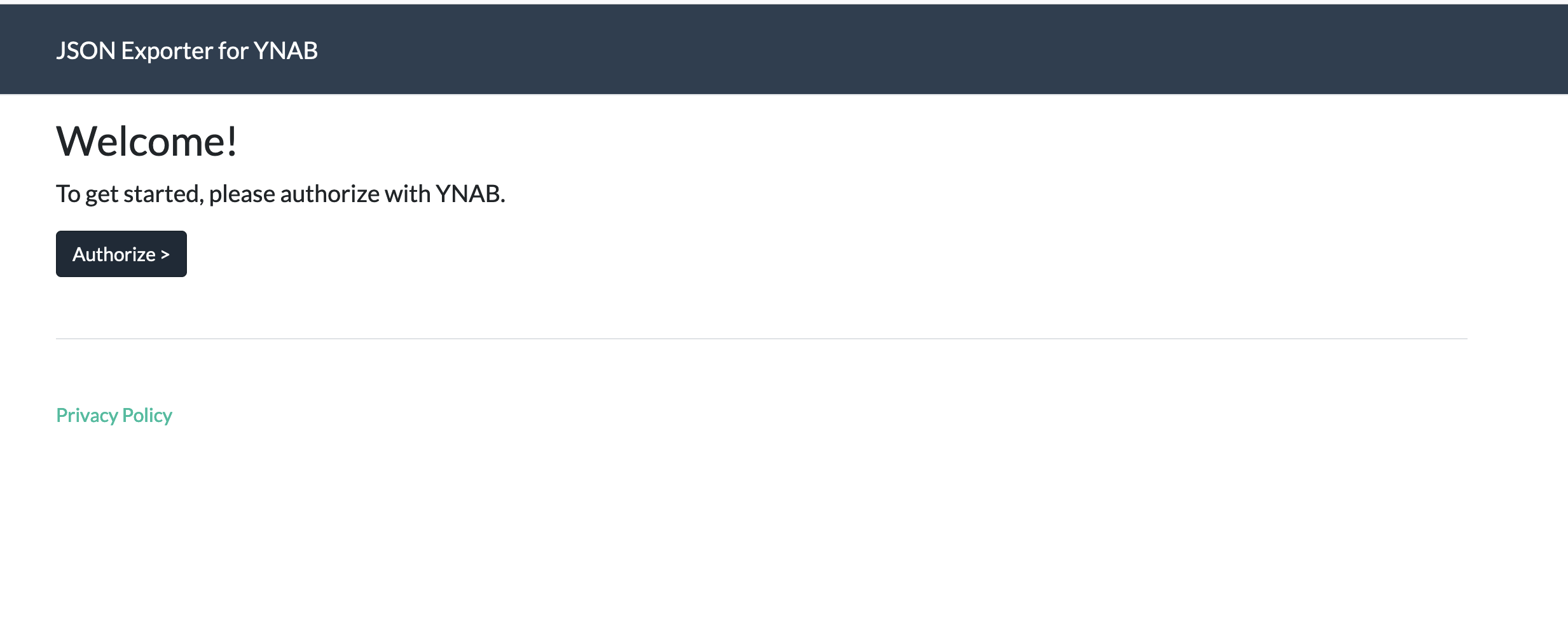

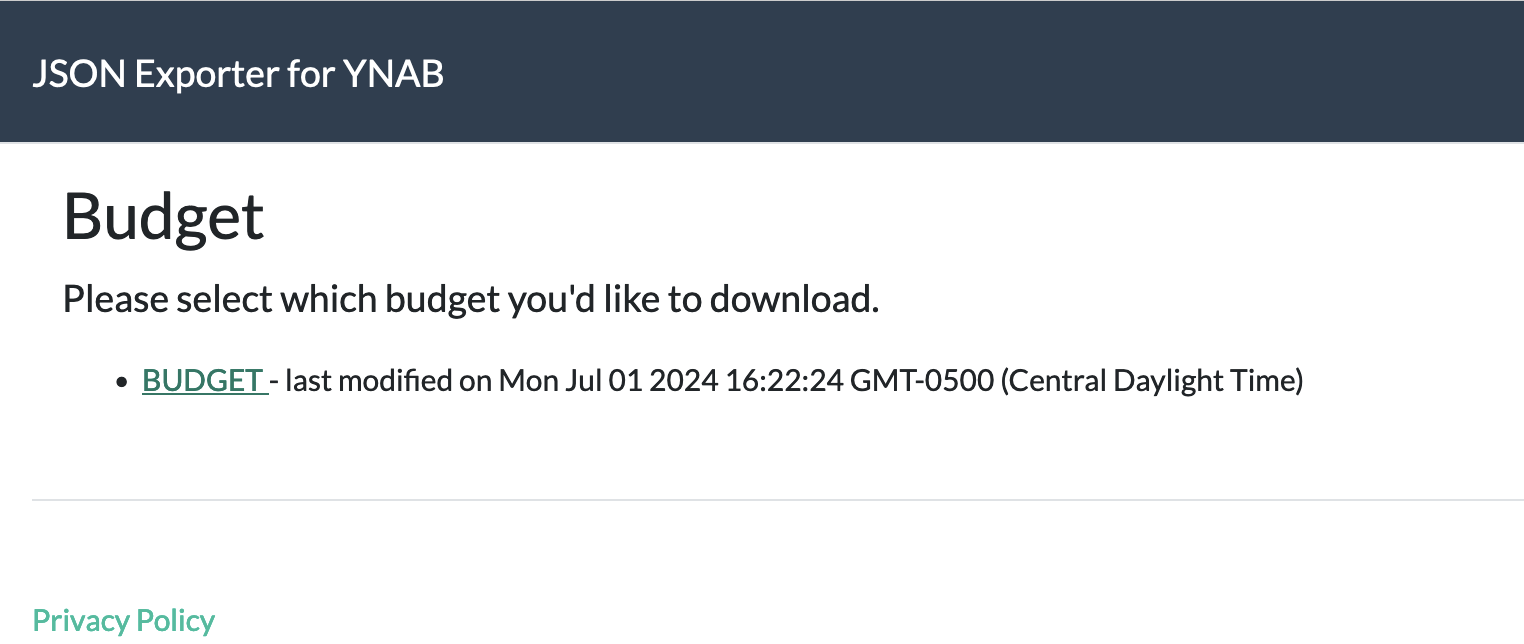

To import your YNAB budget, use this exporter for YNAB.

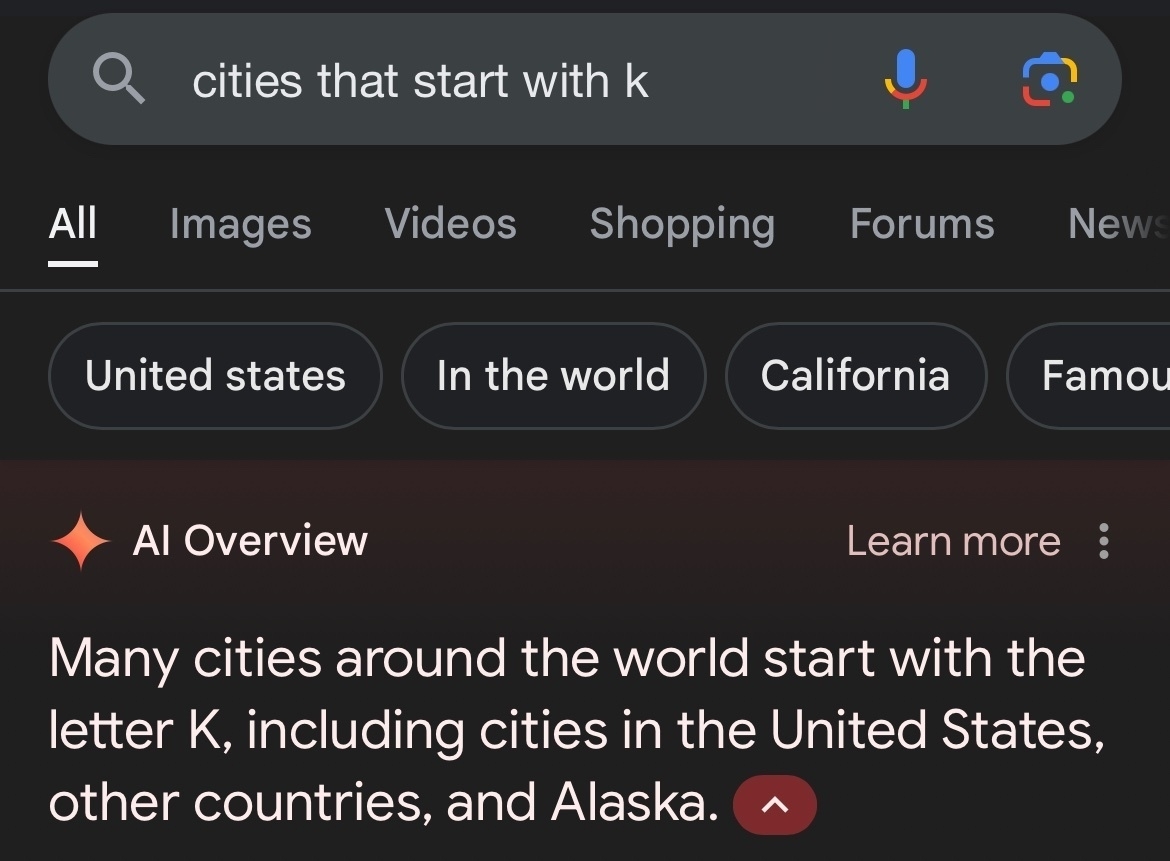

First, click "Authorize":

It'll then ask you to log in with YNAB. After you log in with YNAB, you'll get a screen with a list of your budgets. Click the link on the budget you want to download:

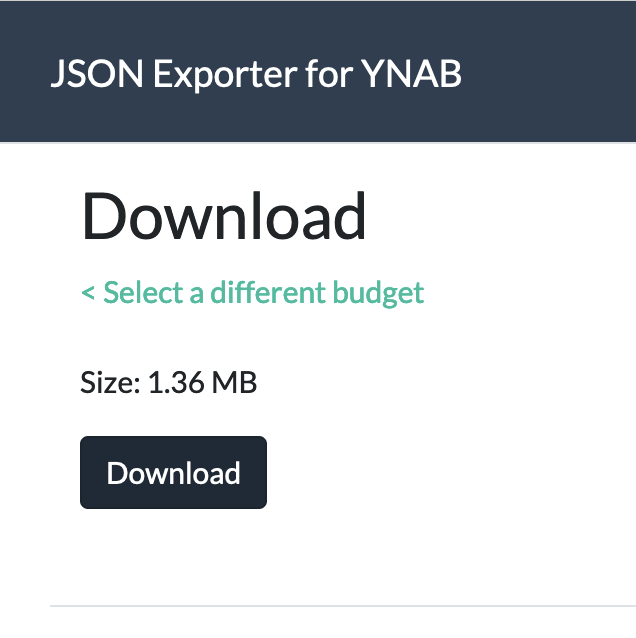

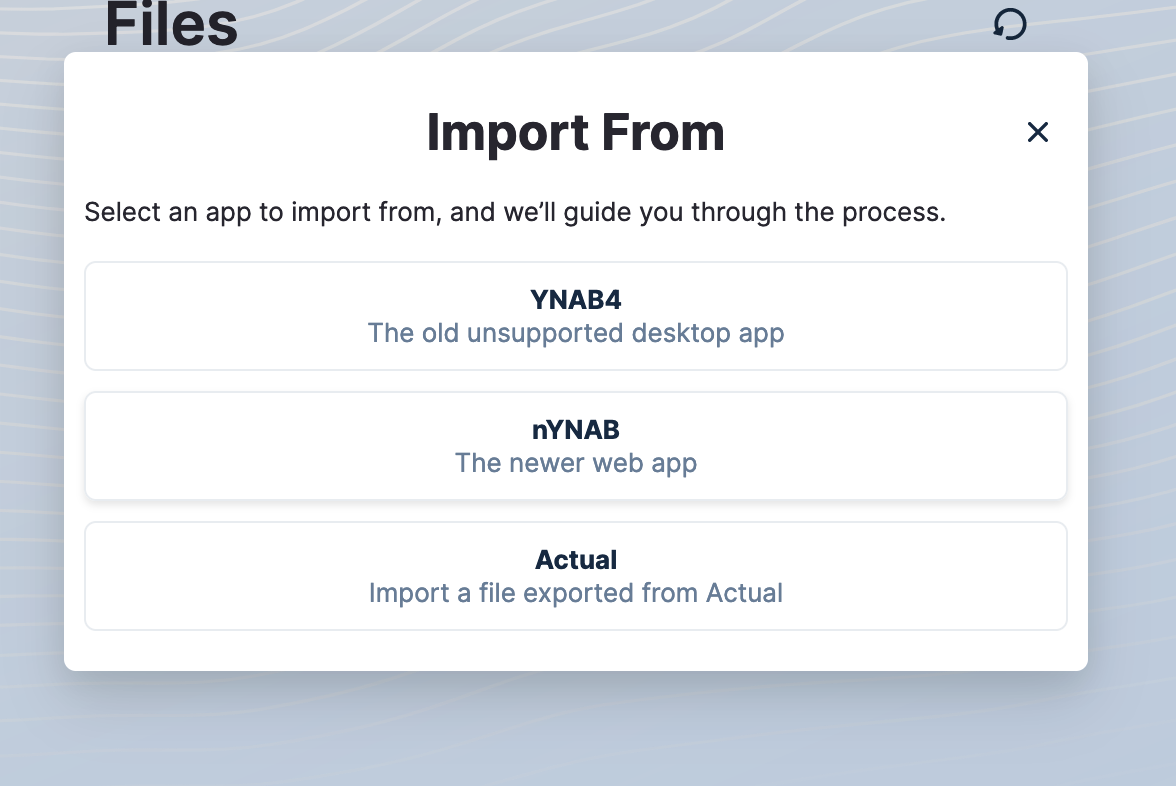

Then click Download:

After you do that, press Import in Actual and import the file you just downloaded. Click nYNAB and select the file:

Now your budget should be loaded into Actual!

Note that you might have to follow these steps to clean up the Ready to Assign for previous months (Actual does this a little differently, as covered later).

Reading the budget

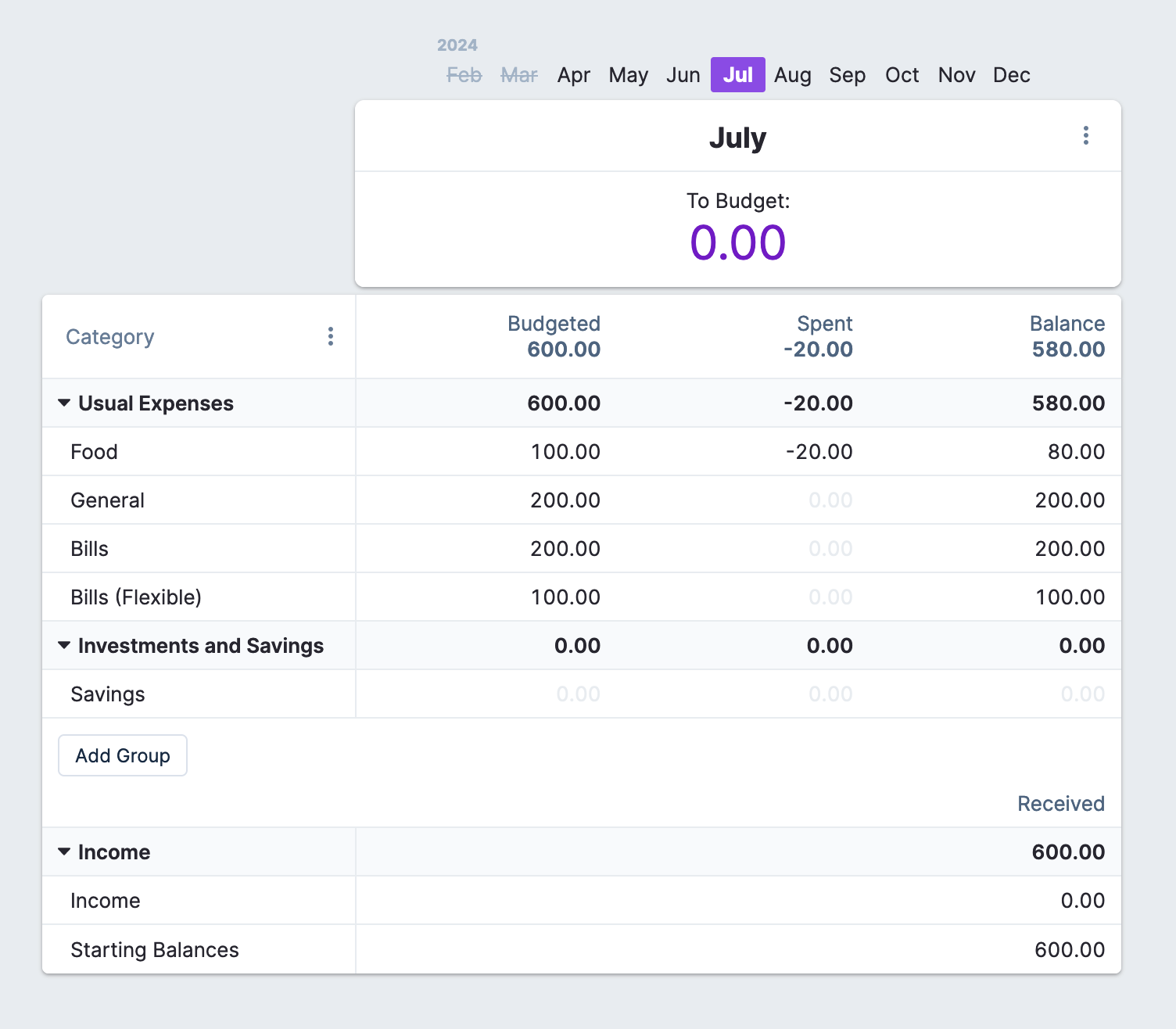

Budgeting in Actual is zero-based, just like YNAB. You only budget with the money you have. However, the budget is laid out slightly differently.

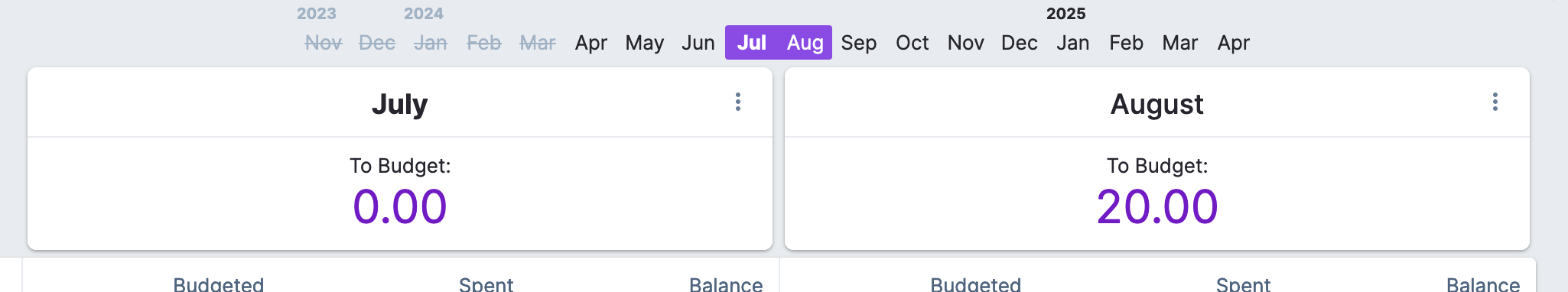

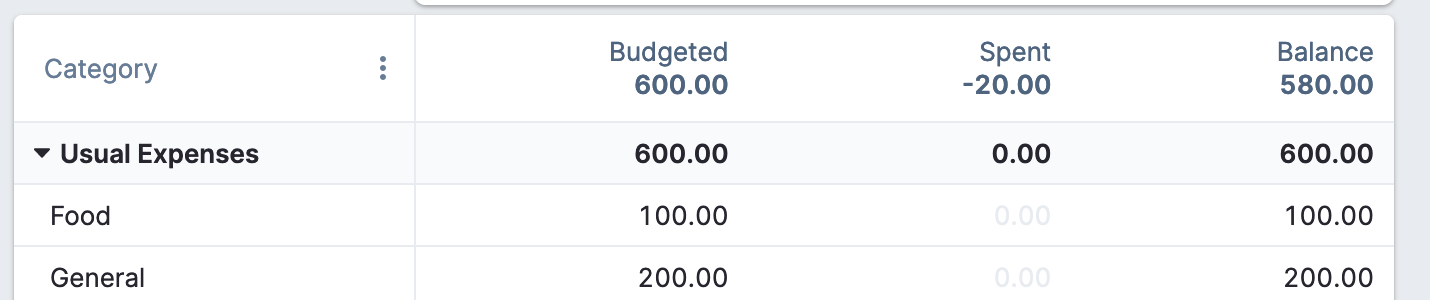

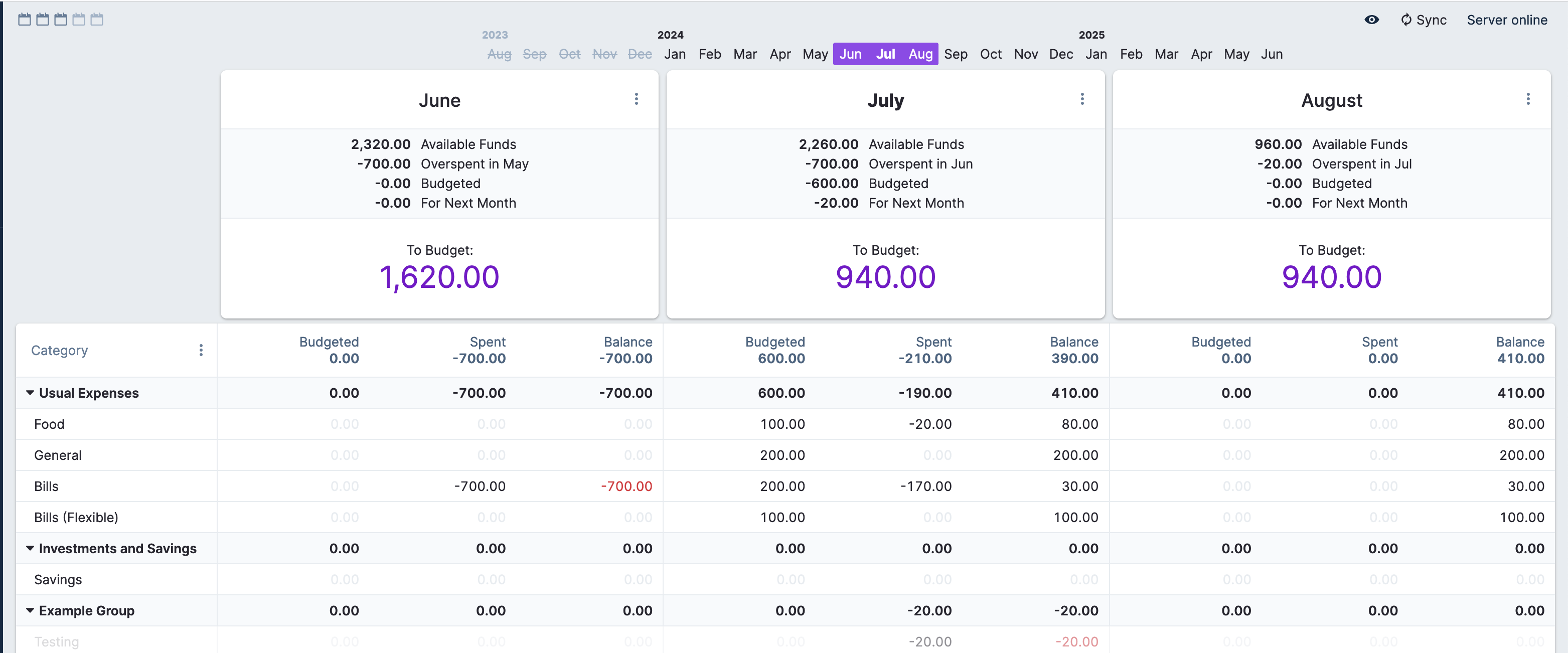

First, the similarities. Actual has a familiar tri-column layout for its budget. The left column is what you've budgeted, the middle column is what you've spent, and the right column is the current balance. The budget has months, and you can see the ready to assign up at the top:

However, there's an immediate difference: actual has income categories.

Income categories

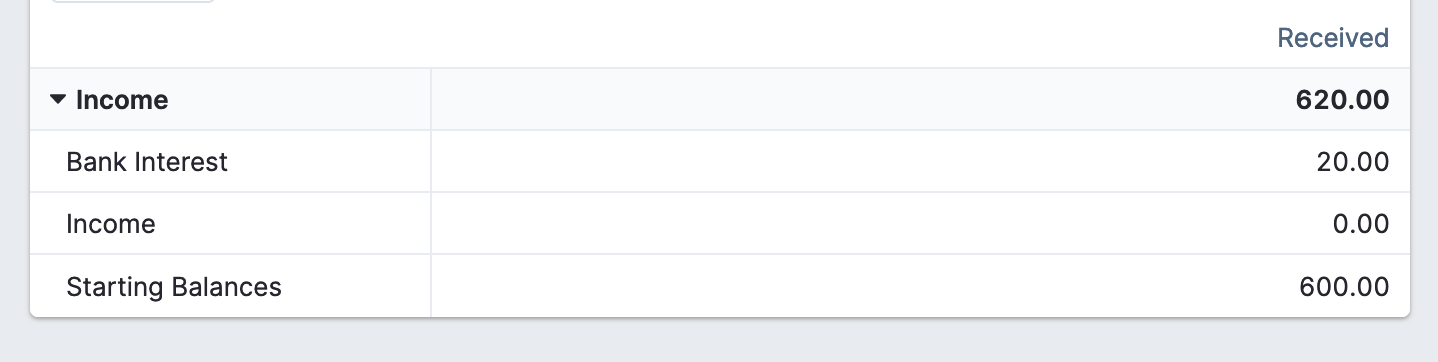

When you receive income in Actual, you can optionally assign it to any of your income categories. Then Actual will show you the income for the month by category at the bottom of your screen.

Here's an example: if I create an 'Interest from Bank' income category and add a transaction for it, Actual updates the category with the amount I received.

This doesn't affect anything else in the budget. All income categories get dumped into the same Ready to Assign for the month. This can be helpful for tracking stuff for taxes, seeing how much you've gotten from friends on Venmo, or other things like that.

To Budget

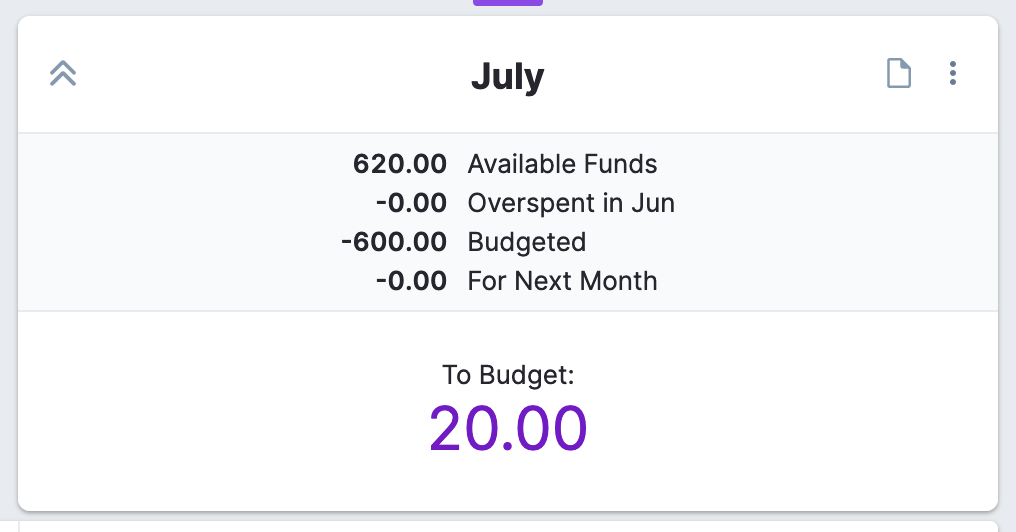

To Budget works just like Ready to Assign does in YNAB. You can click the little dropdown at the upper left of the month to see how it calculates it.

Available funds is all of the income you've received, budgeted is what you've set aside so far, and overspent is all of the money you've overspent in the previous month. However, Actual has one additional feature: you can set aside money from To Budget for future months. This lets you budget this month's income for next month, putting it into next month's To Assign.

In YNAB, you might've done this by creating a rollover category. For example, you might create a "Next Month's Expenses" category and assigned all the money you need for next month to it. This removes the money from Ready to Assign and gets YNAB to stop bugging you about it.

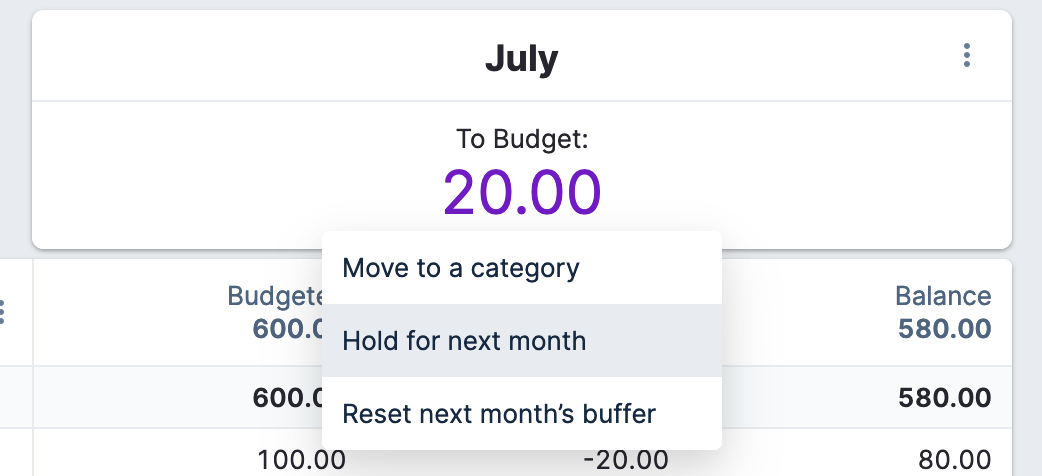

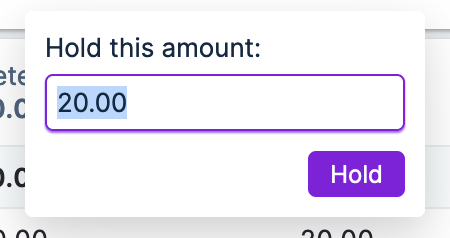

In Actual, you don't need a separate category to do this. Instead, click the To Budget number. In the dropdown that shows up, click "Hold for Next Month" and then enter how much you want to save for next month.

Once you click save, you'll see the to budget for this month go to zero. The To Budget for next month should stay the same.

Oh wait, look! A new feature!

Multi-month view

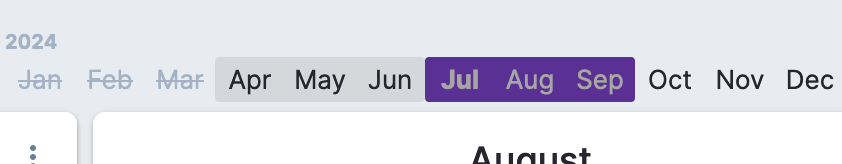

In Actual, you can view the budget for multiple months at the same time. You can set the number you want to view at the upper left hand corner of the screen:

Then when you click on the months you want to view, you'll see a little preview of which months Actual will show you.

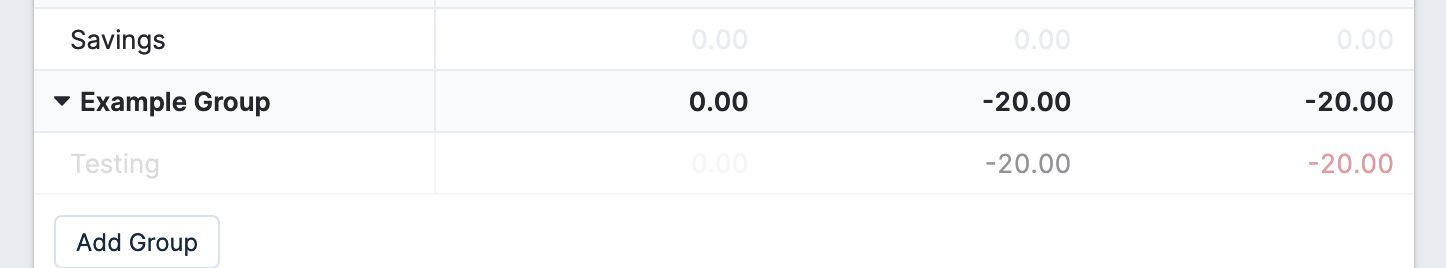

Creating categories and groups

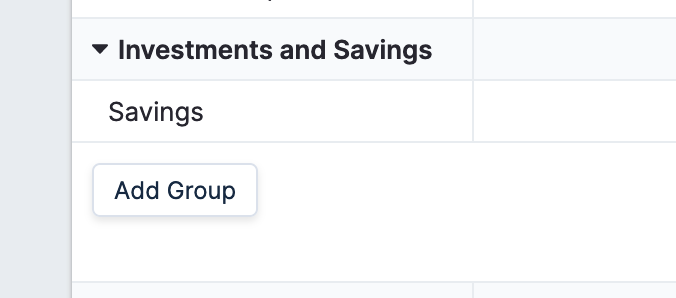

Categories and groups work just like they do in YNAB, with an extra feature or two, click the "Create group" button at the bottom of the screen.

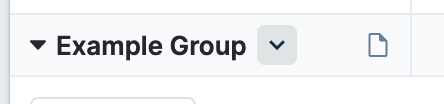

To create a new category, click the down arrow next to the name of the group you want to make it under. Then create it just like you would in YNAB.

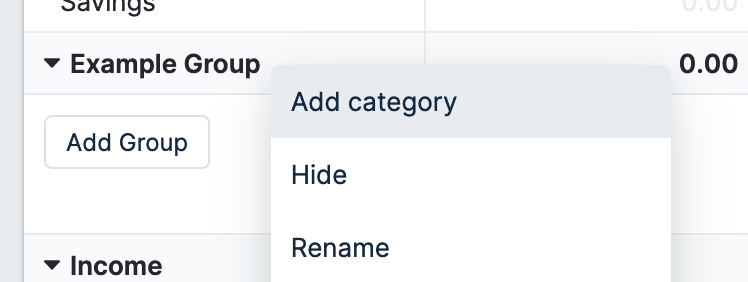

In Actual you can both hide and delete categories. YNAB has gone through different variations of this over the years. Currently it just lets you delete a category. Actual lets you do the same thing, requiring you to move transactions to a different category if there are any.

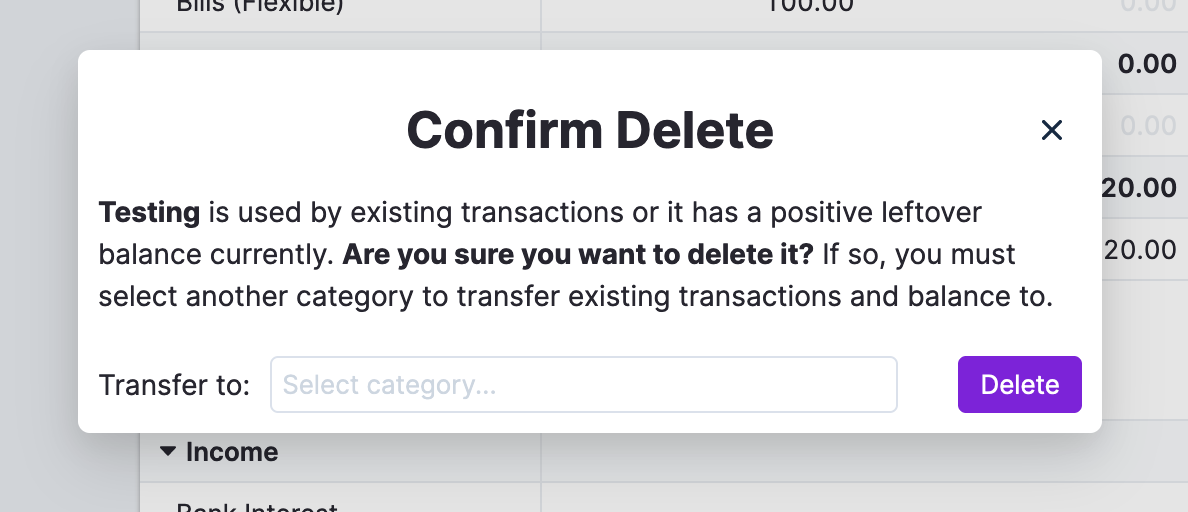

When you hide a category, it gets hidden from the budget. To view it again, click the three dots next to "Categories", then click "Toggle hidden categories". The category will show up in gray.

Accounts

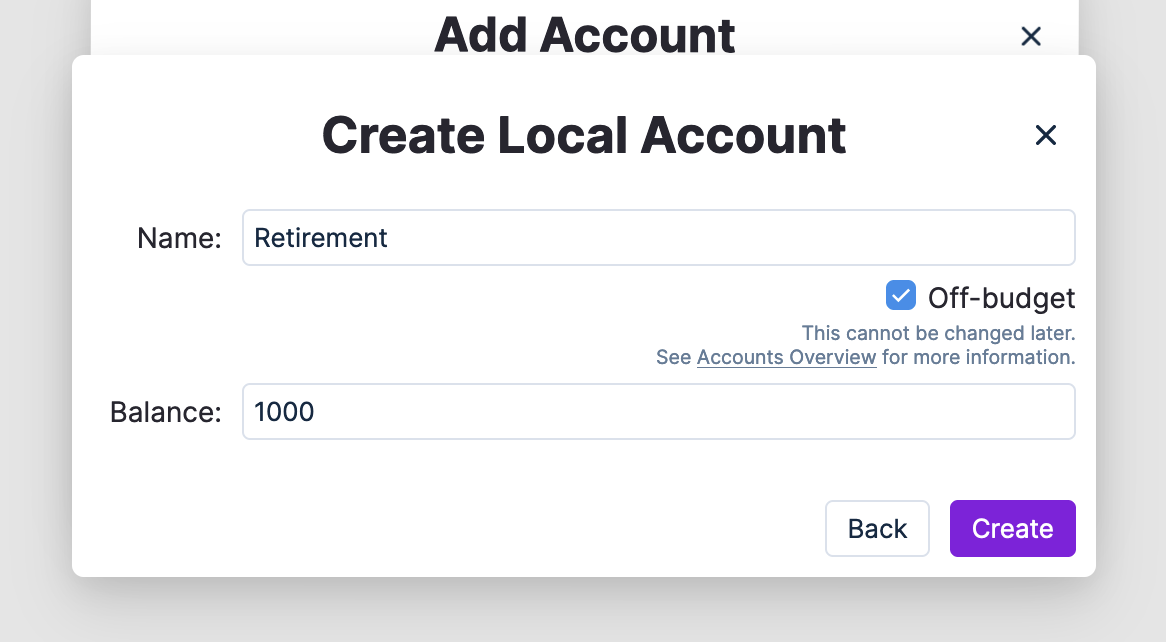

Accounts function the same in Actual as in YNAB, with a few small differences.

First, there are no account types. Just create an account for each of your accounts.

Untracked vs tracked accounts are created by setting the "Off budget" checkbox. If checked, it creates an off budget account (which is the same as an untracked account). If unchecked, it creates an on budget account (the same as a tracked account).

Off budget accounts won't have their account totals included in your budget (hence the name). They will be included in your net worth calculations, just like in YNAB.

Working balance

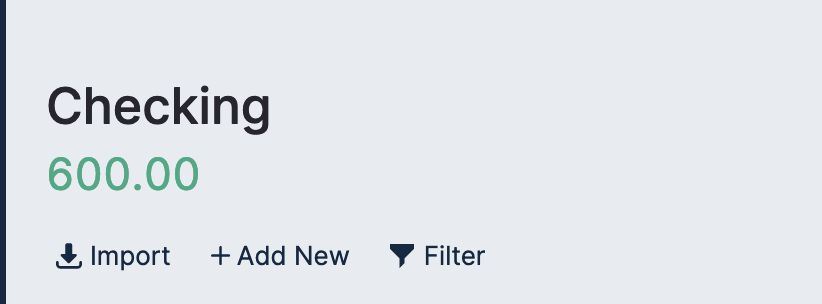

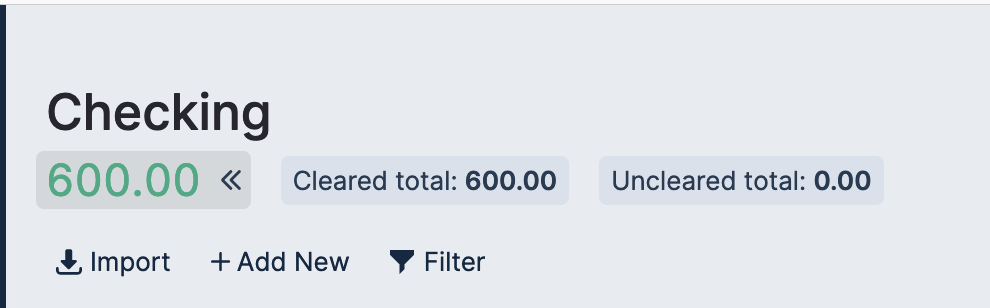

Coming from YNAB, you'll be used to the Cleared Balance, Uncleared Balance, and Working Balance (which is the Cleared Balance + Uncleared Balance). Actual shows the Working Balance by default.

By default, Actual doesn't show the Cleared and Uncleared Balance. When you're looking at an account, click the account total to show the Cleared and Uncleared Balance:

Actual will remember which accounts you've toggled this on or off for. So if you have some accounts where you want to see the cleared and uncleared totals (credit cards, bank accounts), you can enable this for those, and for the rest you can keep the simple working balance (retirement, investment accounts, etc).

Credit cards

Like we covered earlier, there are no account types in Actual. This means that credit cards work differently than in YNAB.

In Actual, there's no categories for each credit card like YNAB has. Instead, you just spend money from the credit card like you would any other account. This is a bit weird, but it makes sense with an example.

Say I have $600 in my checking, and I've set aside $100 for my food budget.

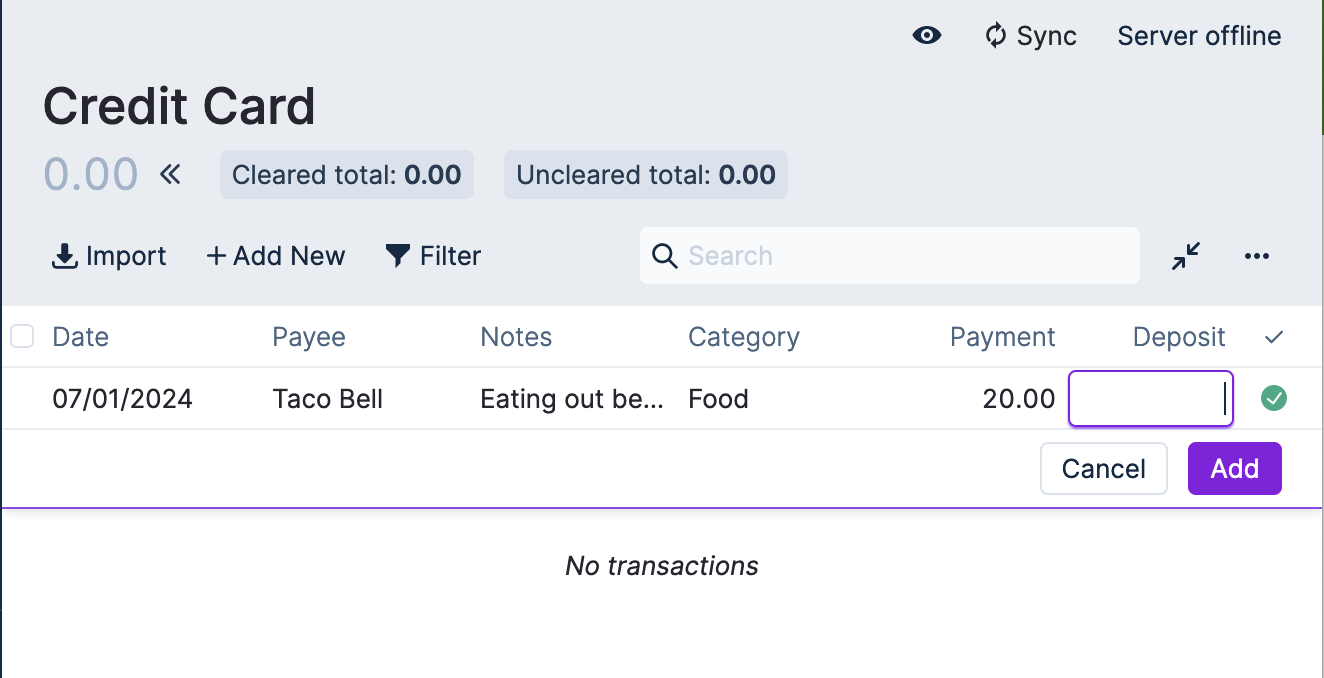

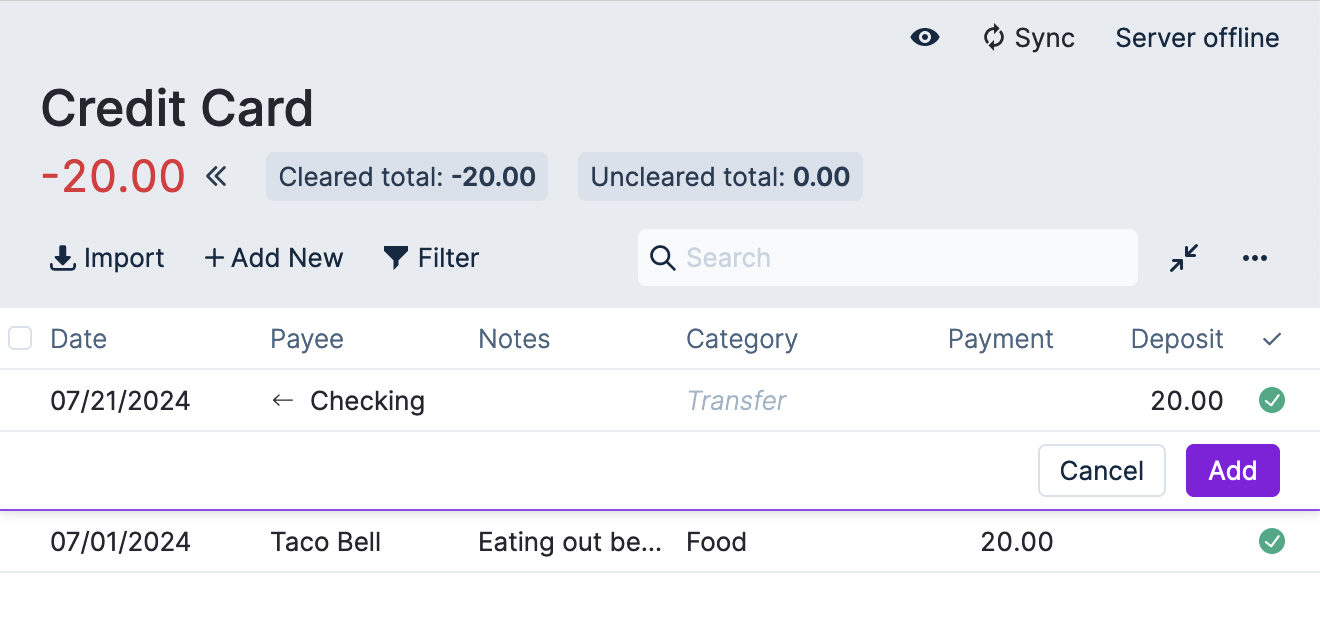

If I buy lunch at Taco Bell on my credit card, I would go into the credit card and input the transaction just like any other transaction:

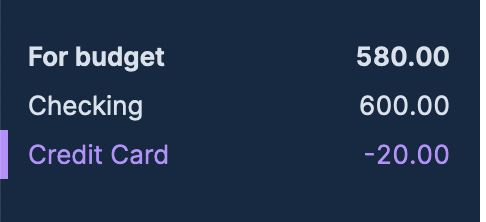

When I click Add, my new account total on the credit card becomes $-20.00 (just like in YNAB). You'll also notice that the "For budget" total has gone down by $20.

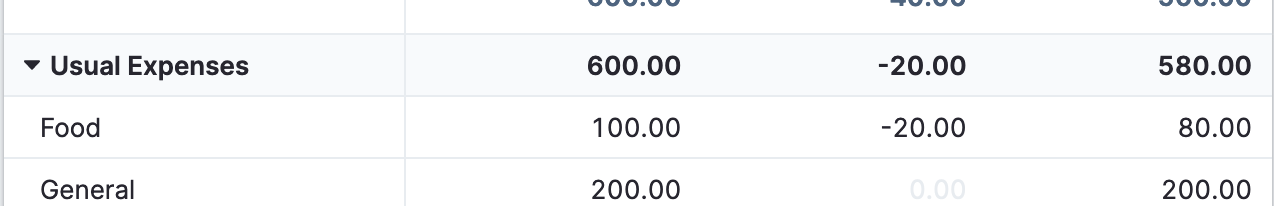

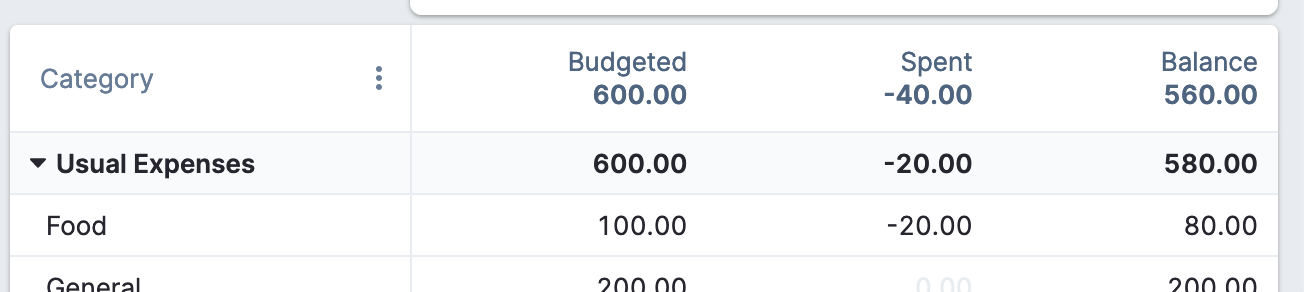

Now when I go back to my budget, I see that my balance in the Food budget has gone down by $20 too.

Instead of creating a new category and moving the money to it, Actual just subtracts the amount you spent from the category itself. Then your payment for the month is whatever your account balance is. In this case, mine would be $20.

Let's fast forward to when my pretend credit card payment happens. I create a $20 transfer from my Checking into my Credit Card. This works just like it does in YNAB:

For bonus points, if you click on the little arrow next to Checking, Actual will take you to the corresponding transaction in your Checking account.

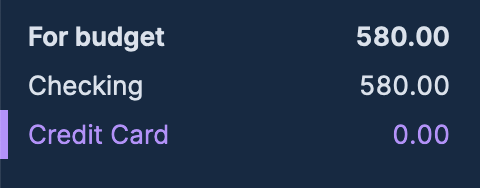

When I add this transaction, my credit card balance goes to zero. For budget in the sidebar doesn't change at all.

And none of my account balances change either because this is just a transfer:

So to recap, instead of transferring money to a special credit card category, Actual will just subtract it from your budget. This lowers the balance of the category. Because the balance of the category is lower (meaning you have less available to spend) but your checking account balance hasn't changed, this means you'll have that money saved for that credit card payment.

Then at the end of the month (or whenever your credit card payment is due), you just pay the full account balance. Because your budget lines up and you haven't overspent, you can be sure the money is all there.

In a lot of ways this is simpler than YNAB's approach. If you're on autopay (like I am), you don't pay attention to these numbers a lot and the credit card categories can often get in the way. My credit card categories always end up overbudgeted for some reason and have a bunch of extra cash in them (either because of returns, cancelled transactions, or other reasons). Actual completely avoids this by getting rid of them and just keeping it simple: when you spend money, regardless of where, it's taken from your budget balances.

Future transactions

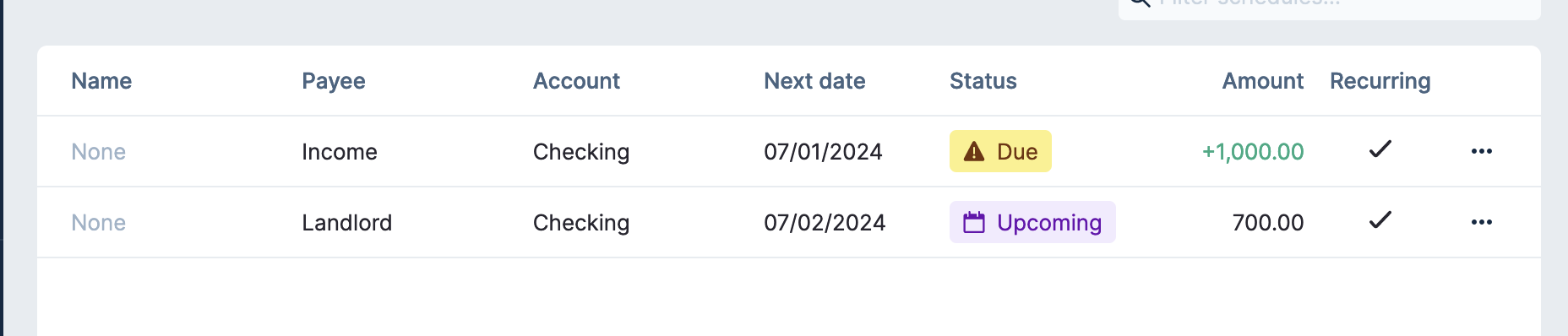

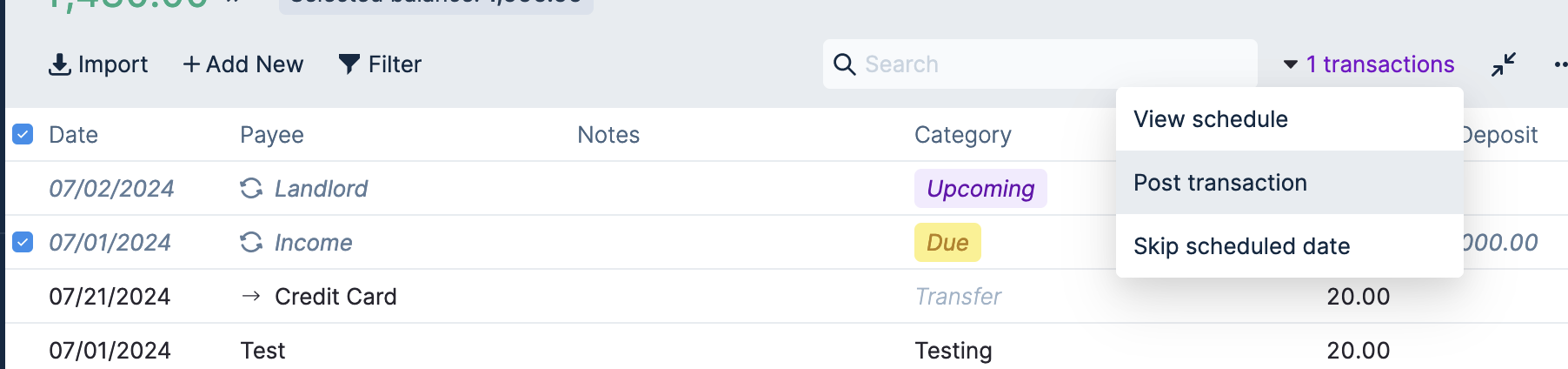

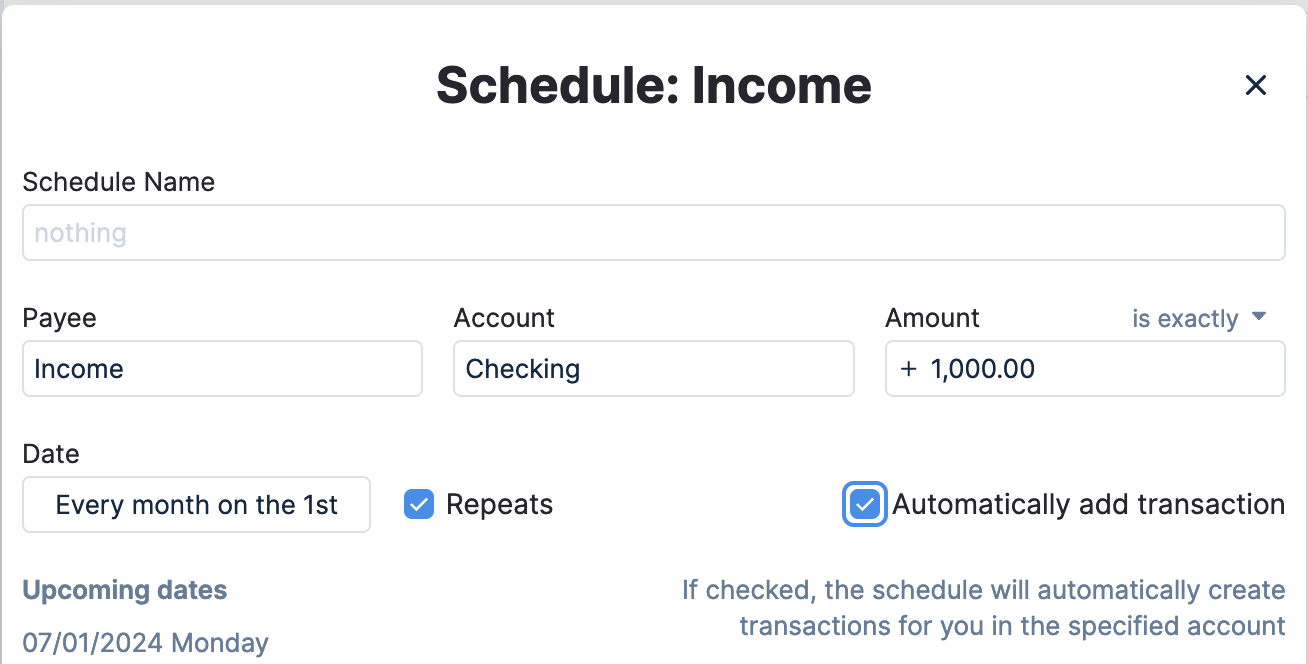

Future transactions are called Schedules in Actual. They work basically the same but are slightly different.

First, they get their own tab in the sidebar:

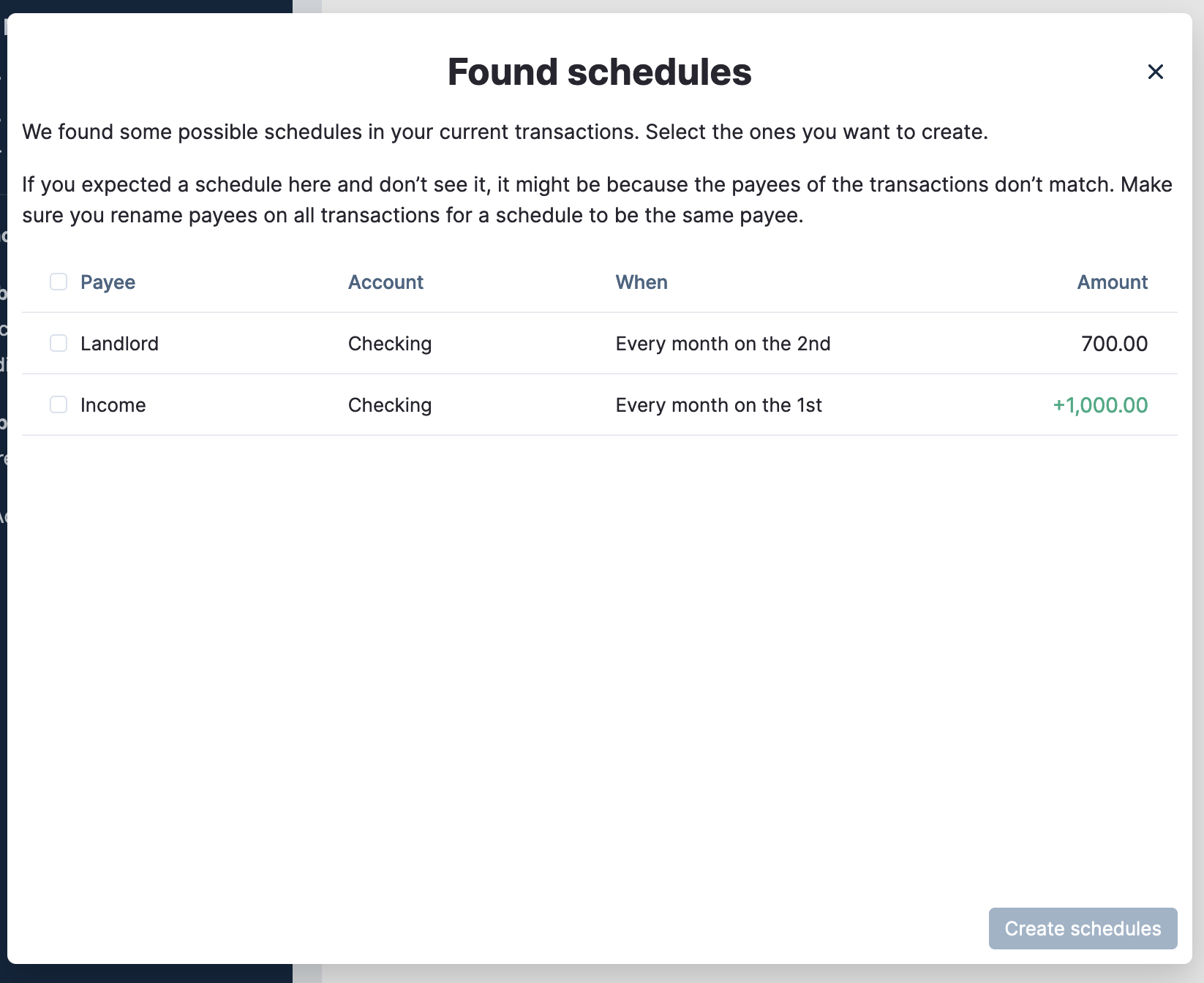

Second, Actual has a feature where it can find some recurring transactions for you. If you click "Find schedules" at the bottom left hand corner of the page, Actual will look through your transaction history and find recurring payments. This isn't just stuff paid monthly, it can even guess your paycheck!

By default, the transactions for schedules aren't automatically created. This is the opposite of how YNAB works. This is for a good reason.

Each of your schedules gets a status. This can be Due, Upcoming, Overdue, etc. This can alert you of transactions that haven't come through yet that should, or transactions that you can expect later this week.

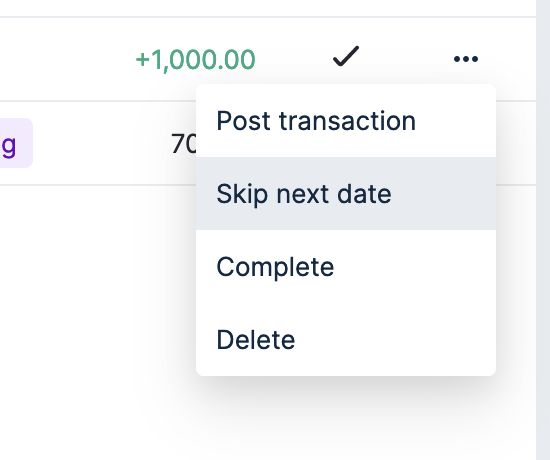

You can also skip transactions if you know they're not going to happen this time around (unlike YNAB):

Creating transactions for a schedule

Transactions for a schedule either get created when you create the transaction yourself (and it'll automatically get linked), or by selecting the scheduled transaction and clicking "Post transaction".

If you really want the behavior of YNAB where it automatically creates the transaction, you can edit the Schedule (by clicking on it in the Schedules tab) and click "Automatically create transaction".

Schedule superpowers

Last, schedules have much more power in them than YNAB with a few extra features.

Do you ever have those transactions that are just ever so slightly off of a perfect schedule? (Mine is electricity.) Schedules come with a few special repeat tools that make it easy to set up more complicated payment structures.

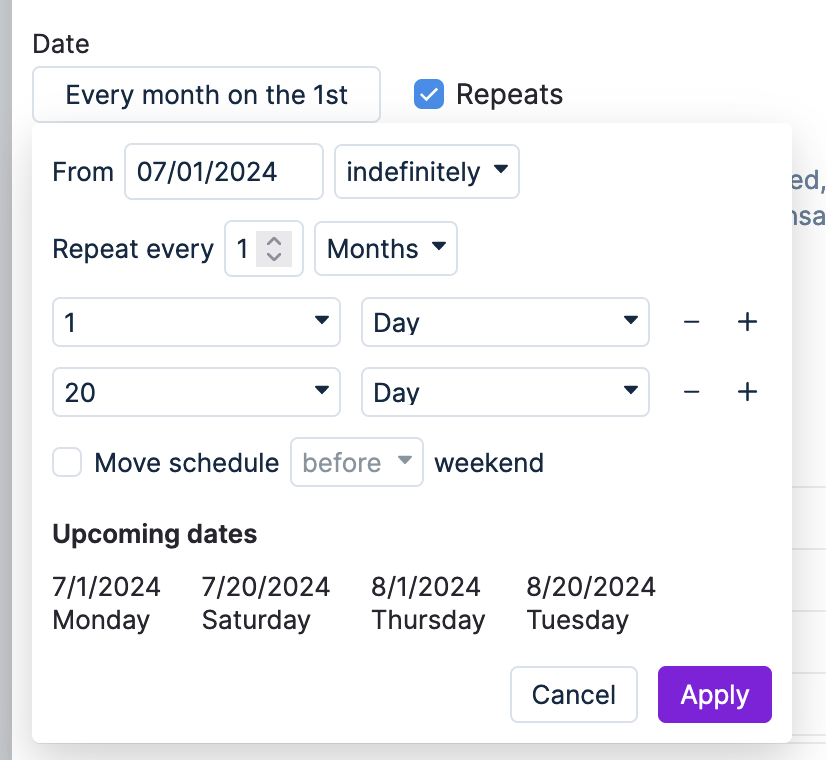

If your payment happens every month, you can set which specific day it happens on. You can also set more than one day. For example, if you get paid on the first and the 20th of the month, you can set that up like this:

Actual will also show a preview of the dates at the bottom of the window for you.

Some transactions only come through on weekdays, not weekends (like ACH transactions). This is how my electricity is billed for some reason. You can tell Actual to skip the weekend by scheduling it before or after the weekend (using the "Move schedule" checkbox).

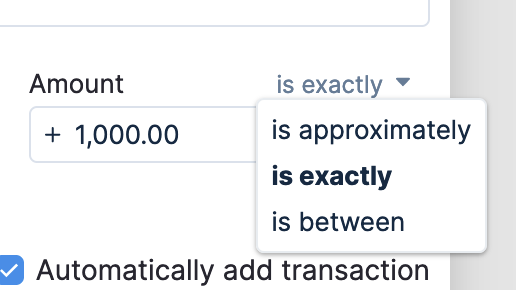

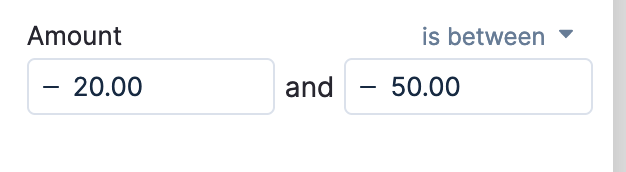

One last little trick (and this is by far the best one): if you don't know exactly what the amount of your transaction will be, you can give Actual an approximation or even a range:

So if you have an electric bill that varies from $20 to $75 some months, you can do it like this:

Then when you create the transaction for this, Actual will still recognize the transaction for the schedule. :D

Payees and Rules

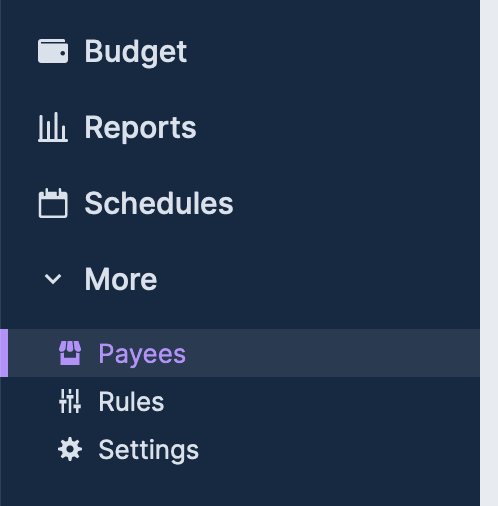

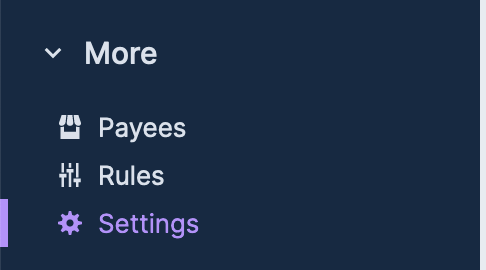

In YNAB, you can edit Payees in the Payees panel. You can do the same in Actual, in the sidebar under More -> Payees.

This looks and works just like it does in YNAB, where you can merge Payees together and delete them if you need to.

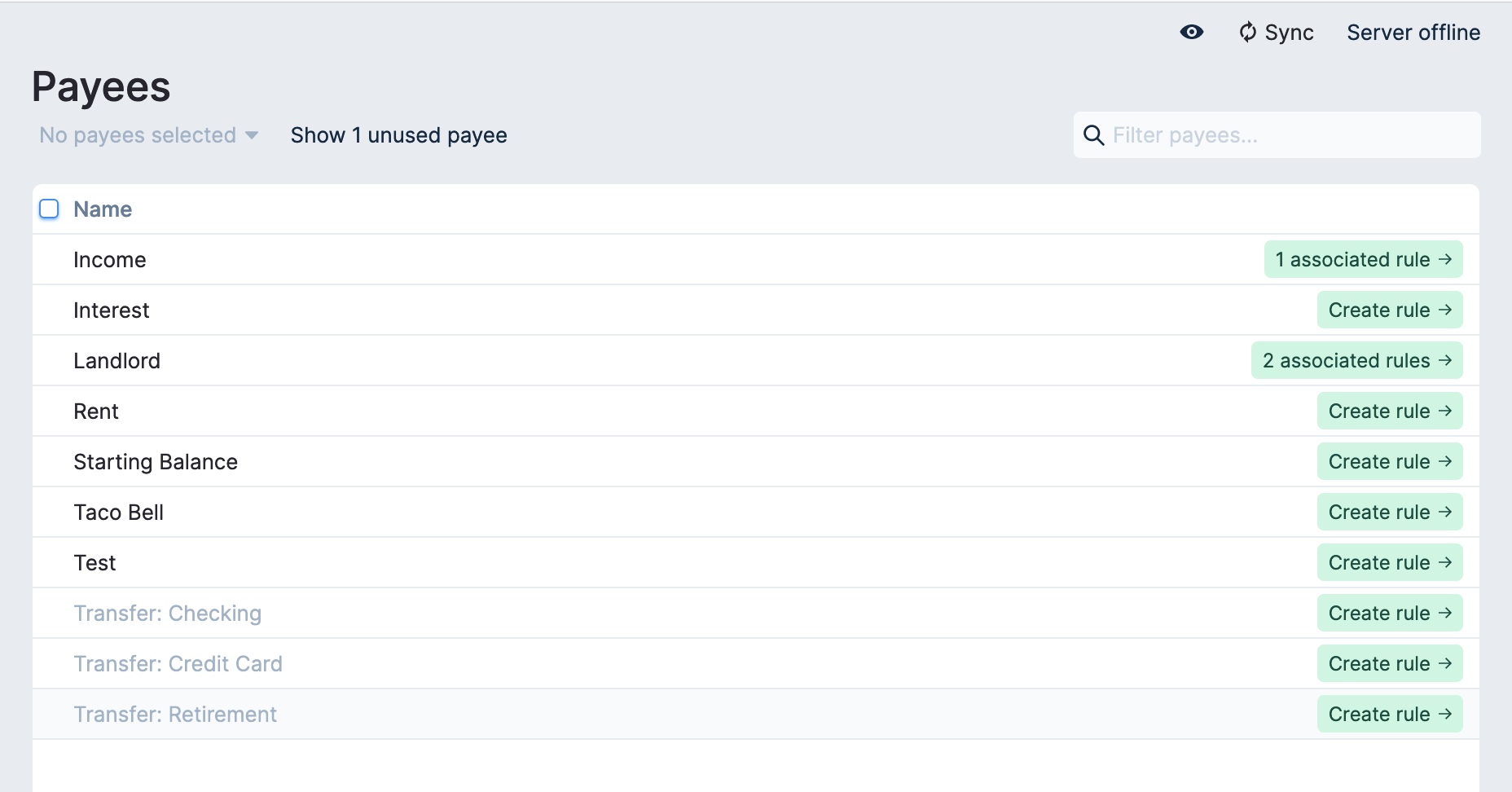

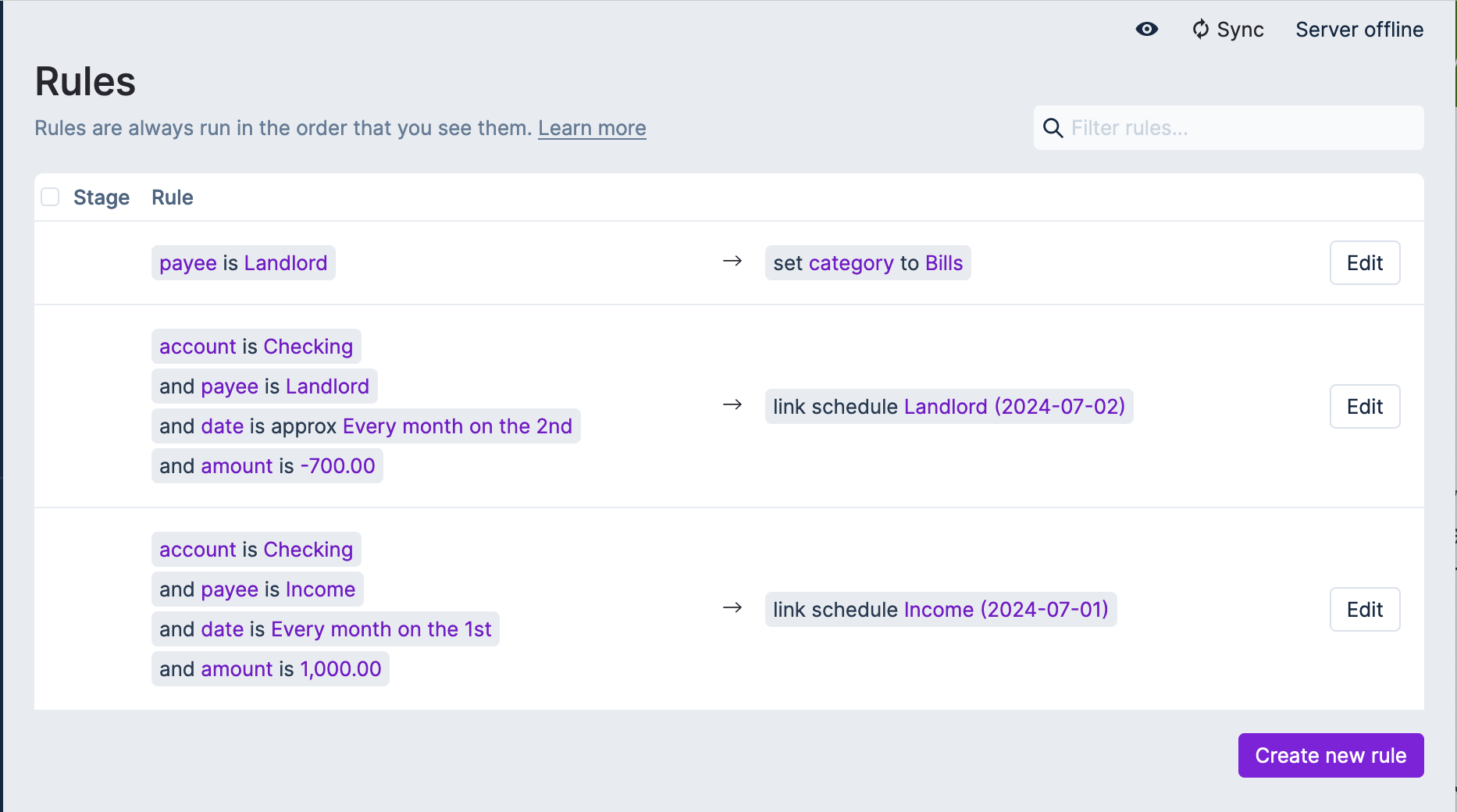

However, instead of automatic categorization and renaming rules like in YNAB, Actual has a single thing called Rules. And they're extraordinarily powerful.

What are rules?

Rules tell Actual what to do to a transaction when it is added. Each rule has a condition and an action. Every time you add a transaction in Actual, Actual goes through alllll of the rules you've told it about. If the condition if the rule matches the transaction you added, then Actual will run the action of the rule.

To see all of the rules in Actual, go to the Rules tab in the sidebar under More.

There you'll see a list of rules like this:

Rules replace automatic categorization and renaming rules in YNAB. But they're also significantly more powerful than anything YNAB offers too. They can save you a ton of time, especially if you're a manual entry person.

Automatically categorizing transactions

Let's try creating a rule for automatically categorizing interest from a savings account (remember, Actual has income categories too!).

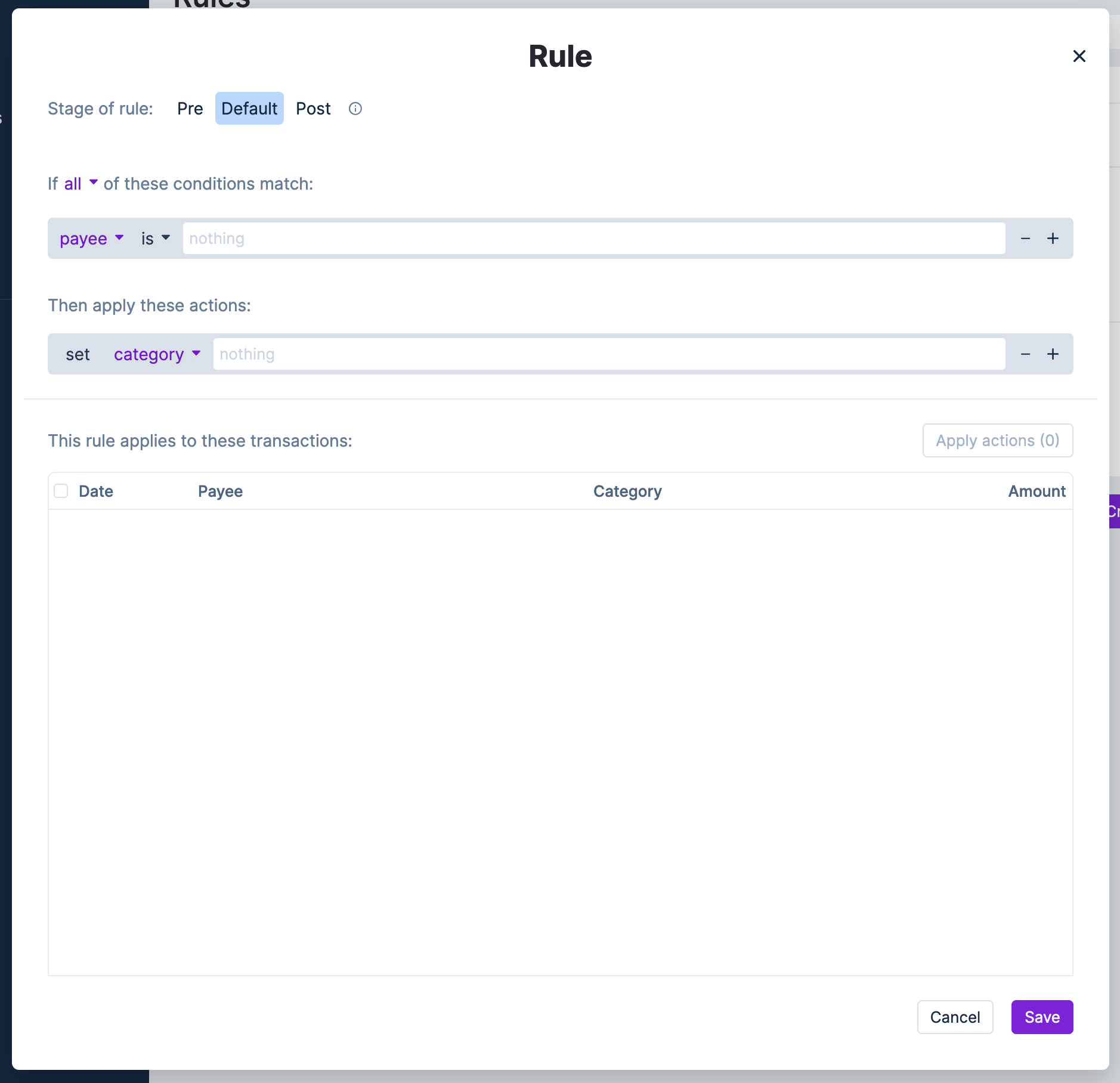

First, click "Create new rule" in the Rules tab. You'll see a window pop up like this:

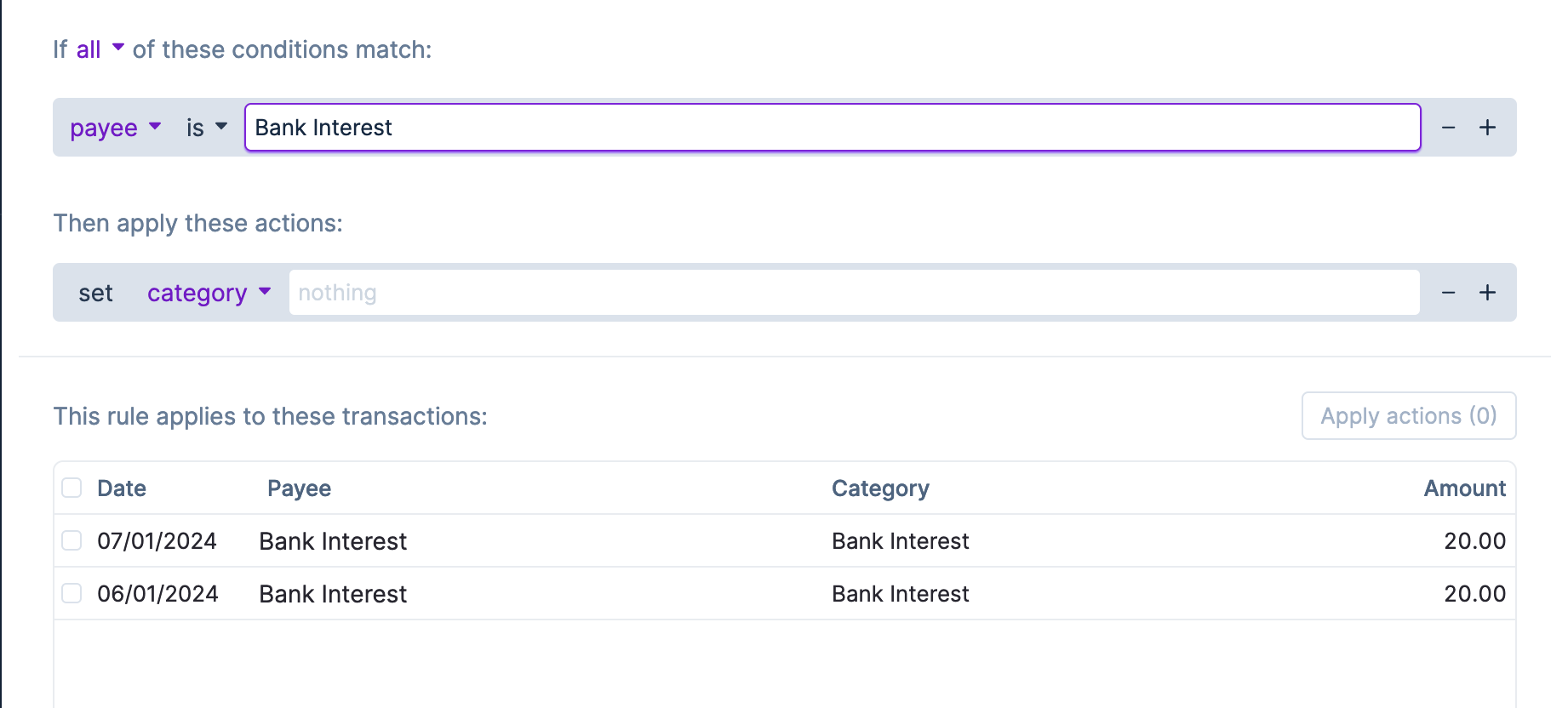

Let's set the payee as "Bank Interest" (the dummy payee I created). As I do that, the table at the bottom of the screen populates with previous transactions that match. This is really useful for making sure you're writing a rule right!

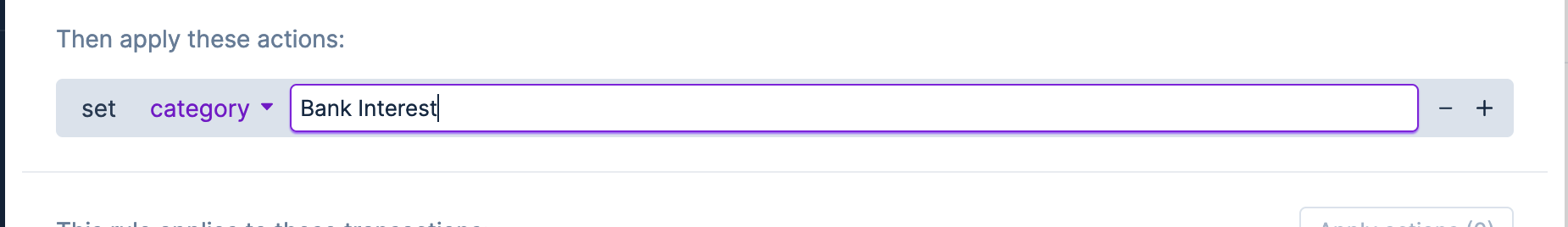

This looks ok. So now, let's set the action to set the category to "Bank Interest" (the category is named the same thing as the Payee for some reason).

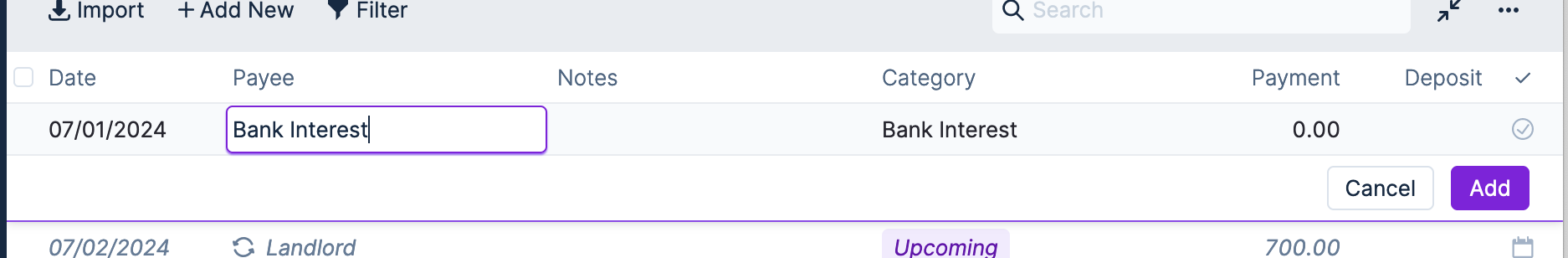

Now if I save the rule and try entering a new transaction for "Bank Interest" in my checking account, the category is immediately set to "Bank Interest":

Renaming payees automatically

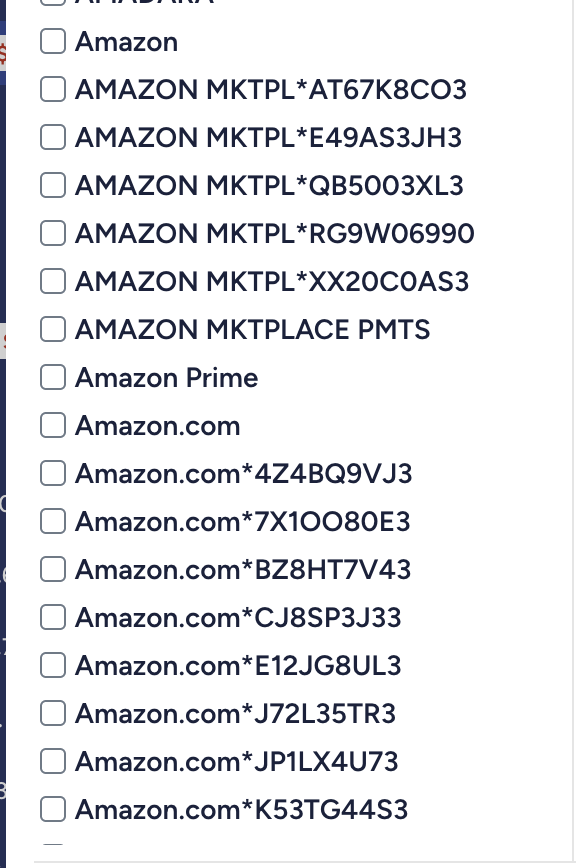

If make a lot of Amazon purchases, you might have a lot of payees that look like this (this screenshot is from YNAB):

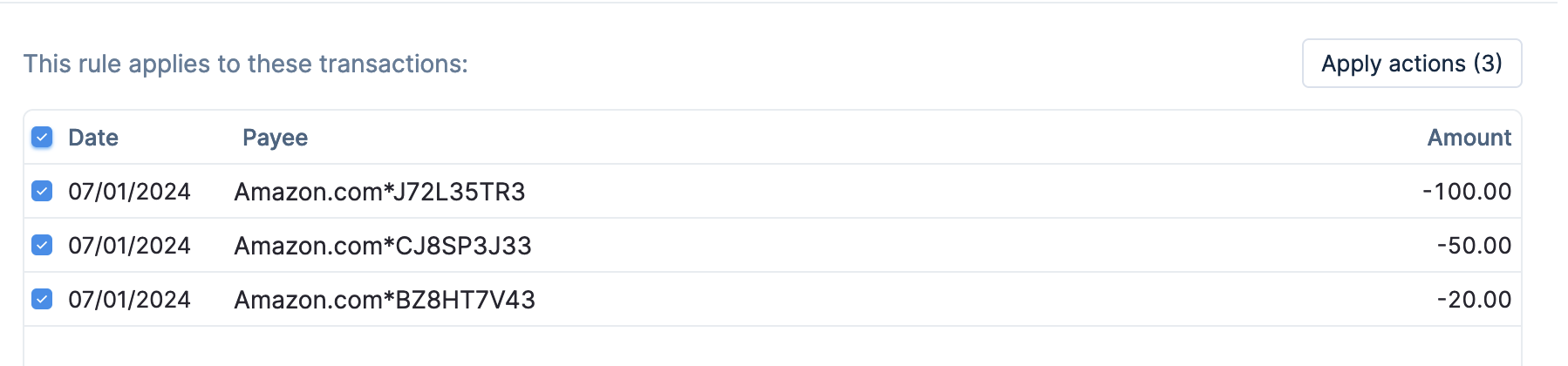

YNAB lets you set renaming rules to match all of these to one payee. In Actual, you just do this with a rule. It looks like this:

We use the "contains" check on the "imported payee" condition. So if the imported payee (either from bank account linking, YNAB import, or bank file imports) contains the word "Amazon", Actual will set the payee to Amazon.

If you have a lot of transactions like these from your YNAB import, you can tell Actual to go ahead and apply the rule to all of the transactions:

Automatically categorizing transactions from the same payee

How do you automatically categorize transactions from the same payee? By spending money from different accounts!

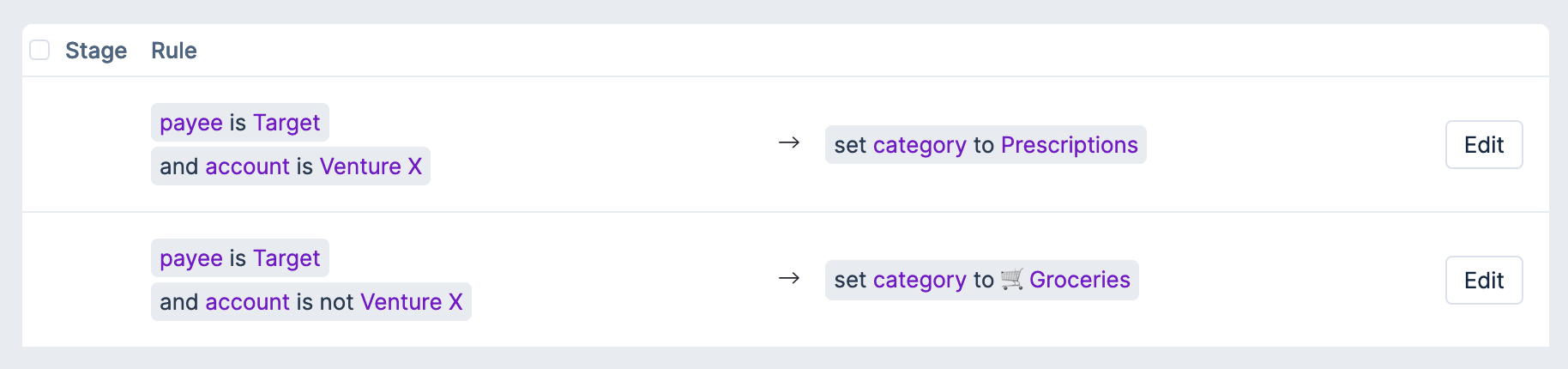

Here's an example. I get my prescriptions from a CVS Pharmacy inside of Target. I also sometimes buy groceries at Target. I want my prescriptions to come out of my Prescriptions category, and my groceries to come out of my Groceries category.

YNAB can't do this out of the box, so I have to categorize each transaction manually as I enter / import it. To get this to work in Actual, all I have to do is spend the money on two separate cards: one for prescriptions, the other for groceries.

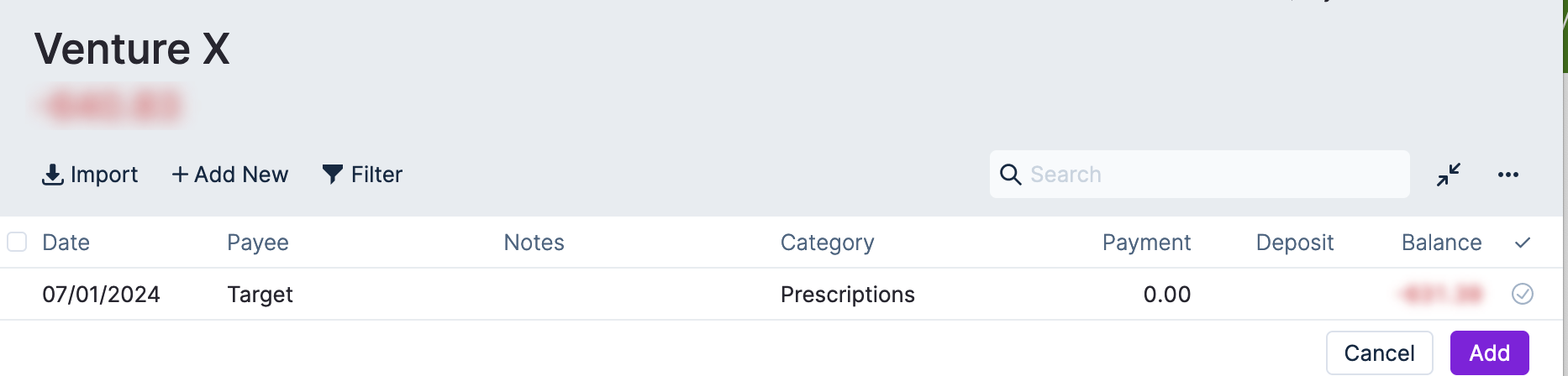

In Actual, we can set up two rules like this:

Now any transactions I add to my Venture X card will automatically be set as prescriptions:

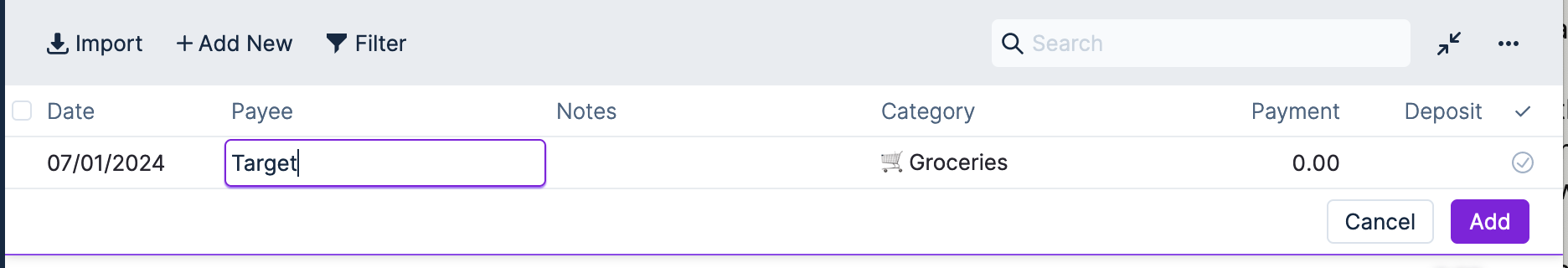

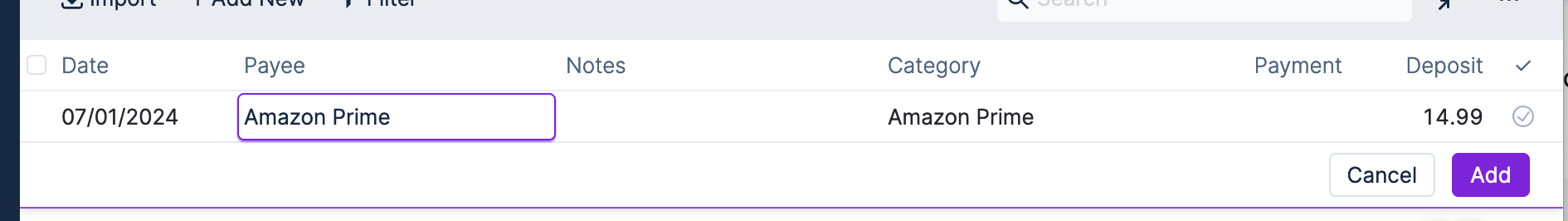

And now anything I add on my other cards is tagged as groceries:

Setting transaction amounts

What about transactions that happen regularly but don't have a schedule? You can also get Actual to set the amount for you. Here's an example of a rule where whenever I add a transaction from Amazon Prime, Actual automatically sets the amount to 14.99:

Now when I create a transaction with Amazon Prime as the payee, the category is set right and the amount is instantly set to 14.99:

This is great for things like subscriptions where you don't want to create a schedule, or for things like public transportation payments where the ticket price is always the same. All you have to do is set the Payee, and everything else is set right :)

Targets

YNAB lets you set targets for categories so you can painlessly save for them easily over time. While Actual doesn't have this feature exactly as implemented in YNAB, it has some things that are similar to it.

Multi-column view

First, do you really need a target? Sometimes you can get by just by looking at two or three months at the same time. For example, I could set my food budget for next month by looking at last month's spend and this month's budget, then coming up with a new number:

All I have to do is look at the numbers that are on the same row. For monthly bills with consistent pricing, this should work for the most part.

Template goals

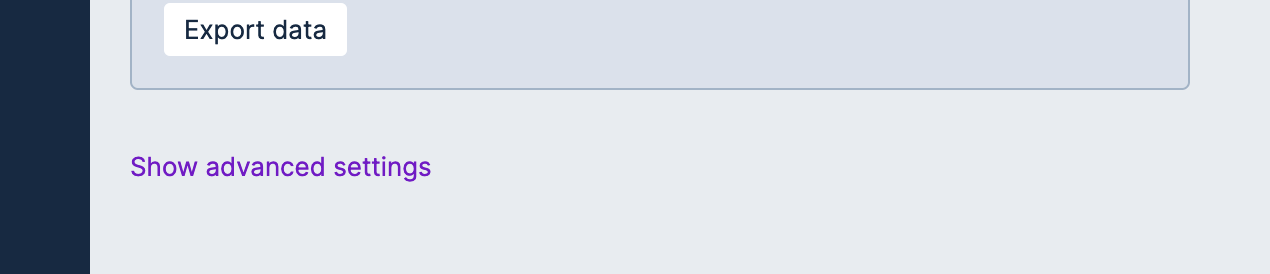

Actual has an experimental feature called Template Goals that are similar to targets. Note that this feature is experimental and won't show up by default. To enable it, go to More -> Settings:

Click on "Show advanced settings":

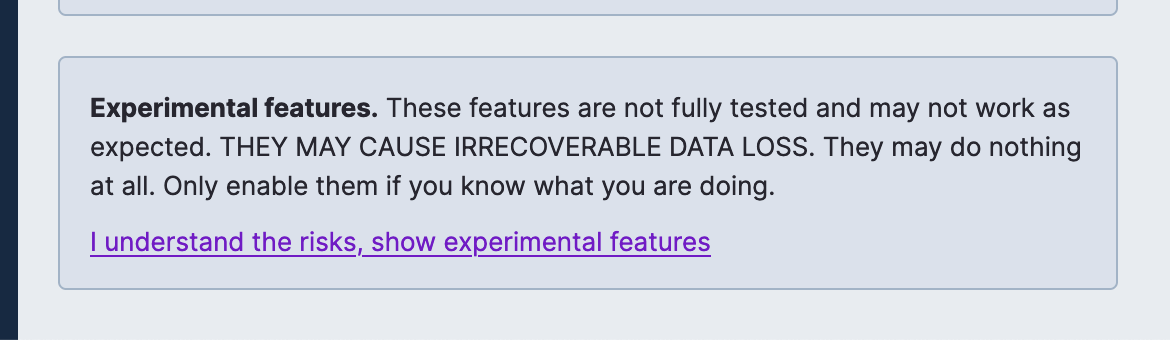

Then scroll down and click on "I understand the risks, show experimental features":

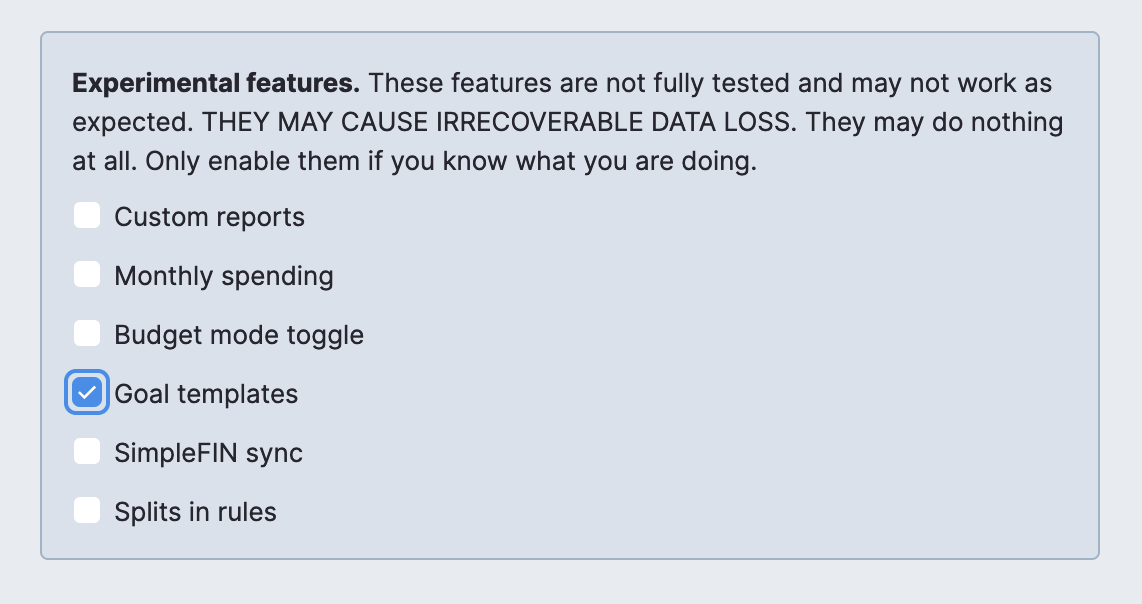

Then select "Goal templates":

Writing template goals

Because template goals are experimental and very early, they don't have a great GUI yet. The Actual devs intent to have a GUI for them before they become not experimental. For now, this means you will have to write some text.

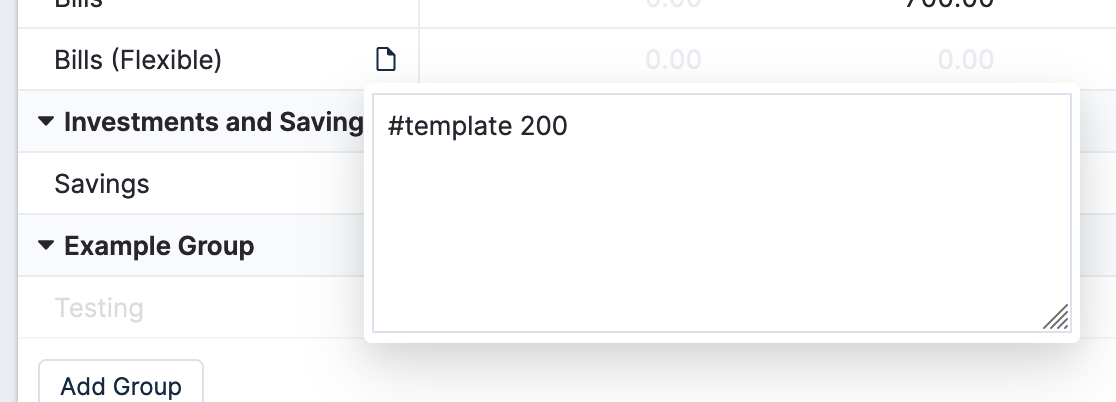

You can create template goals by adding text to the Note of a category. The simplest goal looks like this:

This will tell Actual to set aside $200 each month. This will happen regardless of the balance in the category.

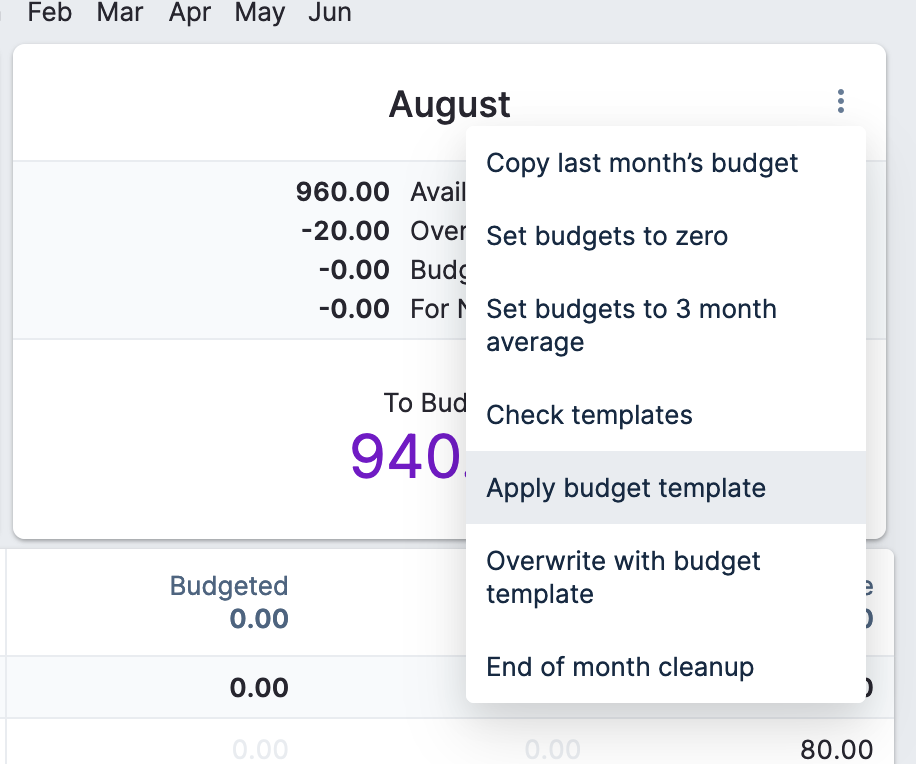

To do the equivalent of Auto-assign in YNAB, go to the upper right hand corner of the month, click the three dots, and click "Apply budget template".

This will go through each of your template goals and assign the relevant amount for them for the month.

Goals and schedules

By far the most useful feature of template goals is that you can link them to a schedule. For example, you can link your Rent category to your Rent schedule via a template goal.

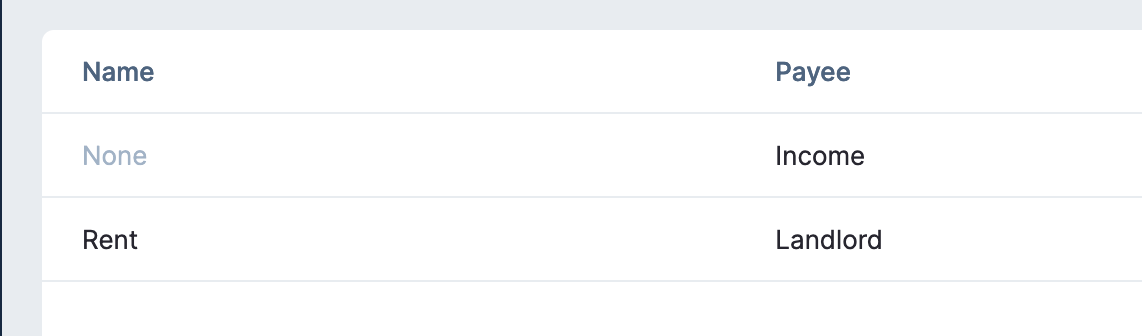

First, make sure your schedule has a name (Schedules -> Click on the schedule to edit -> Name).

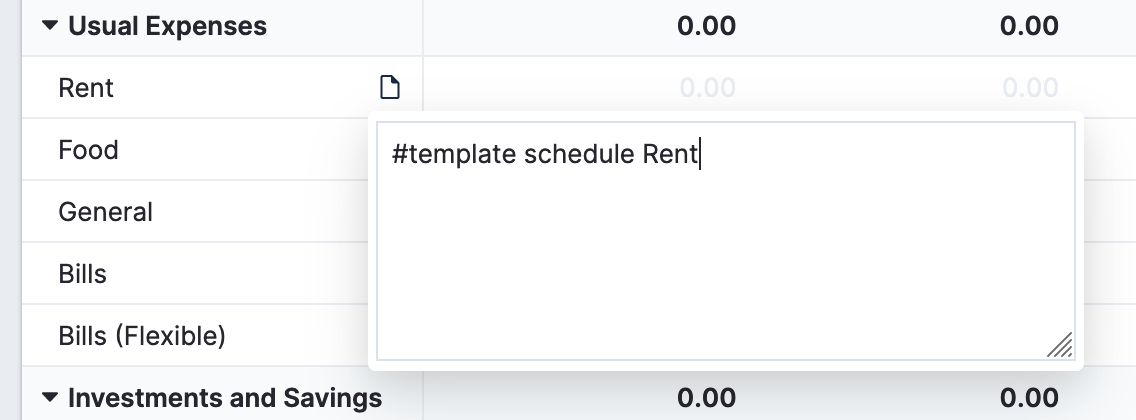

Next, in your category that you want linked to the schedule, set the note to be this:

The format is #template schedule , where

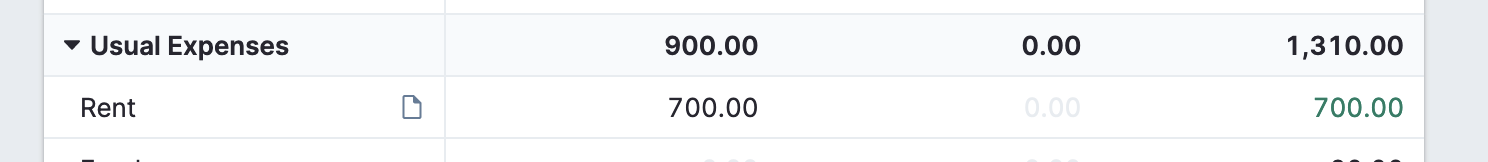

Now when you go to auto-assign, Actual will automatically calculate exactly how much you need to save based on the Schedule:

This works as a temporary workaround to the lack of a GUI for stuff :)

More complicated templates

There is a LOT more you can do with templates, like setting the equivalent of savings goals or spending goals. I'd recommend looking through this table to look at the syntax and what all you can do. Use the "Check templates" button in the budget to validate that you wrote your templates right.

For now, remember again that this is experimental and might not work how you're used to with Auto-Assign. For example, the apply button will overbudget because it sets all the templates. It's not smart about how it does it like YNAB is. So you'll need to zero out ones you want.

Wrapping it up

That's about all of the things you need to know about Actual coming from YNAB, just off the top of my head. If you have any questions, please let me know! I'm really enjoying Actual so far and will likely stick with it.

I asked ChatGPT to rewrite Starships by Nicki Minaj as a legal contract.

I asked ChatGPT to rewrite Starships by Nicki Minaj in the form of a contract agreement. Here it is.

[Article 1: Agreement Pertaining to Coastal Recreational Activities]

1.1 Parties to this agreement (hereinafter referred to as “the Parties”) hereby express their intention to venture forth to a coastal geographic location, commonly known as “the beach,” for the primary purpose of engaging in activities related to oceanic wave interaction.

1.2 The Parties shall maintain autonomy of action and decision-making irrespective of external opinions, commentary, or potential judgments from third parties or public observers, in accordance with the principle of personal liberty and freedom of expression.

1.3 Authorization is hereby granted for the consumption of malt beverages, specifically those labeled as “Bud Light,” within a celebratory context, including but not limited to actions commonly referred to as “toasting” or “clinking of drinks.”

1.4 Recognition is hereby made of the rarity and unique nature of certain participants within this agreement, particularly those possessing qualities of distinction and noteworthiness, including but not limited to social, professional, or personal achievements.

1.5 Engagement in the consumption of distilled spirits, specifically Patrón tequila, is sanctioned and encouraged within a designated area, to be referred to as “the consumption zone.” Participants hereby acknowledge their full and enthusiastic participation in said zone.

1.6 The Parties agree to exercise discretion in the provision of gratuities for services rendered during the course of these activities, with a suggestion towards generosity, notwithstanding their prerogative to utilize personal funds for non-essential or discretionary expenditures.

[Supplementary Section A: Dance Floor Utilization Protocol]

A.1 The signatories to this document (hereinafter “the Signatories”) declare a profound and enduring interest in engaging in rhythmic physical movements, henceforth referred to as “dance activities,” primarily conducted on designated dance surfaces or “floors.”

A.2 It is requested by the Signatories that such dance activities be intensified and continued until such time as physical endurance or capacity may be fully expended, highlighting the potential uniqueness and unrepeatability of this opportunity.

A.3 An open and standing invitation is hereby extended to all relevant parties for increased participation in the aforementioned dance activities, emphasizing the potential for enhanced enjoyment and social engagement.

[Article 2: Directive on Aeronautical Ambitions and Elevation Intent]

2.1 It is hereby acknowledged and agreed that spacecraft, colloquially and hereinafter referred to as “starships,” are constructed with the explicit function and capability of ascending beyond the terrestrial atmosphere and into outer space.

2.2 Participants are encouraged to engage in a symbolic act of raising their upper limbs towards the celestial sphere, signifying aspirations towards said aeronautical ambitions and reflecting the elevated emotional and psychological state of the participants.

2.3 There exists a mutual and binding commitment amongst the participants to persist in these activities, reflecting the elevated state of enjoyment and a collective decision to preclude any consideration of cessation.

2.4 The Parties hereby affirm their intent to repeatedly engage in these activities, reinforcing the significance and desirability of such repetition.

[Sub-Article 2.1: Affirmation of Elevated Status]

2.1.1 The Parties collectively acknowledge and affirm their metaphorical elevation in terms of emotional, psychological, and social excitement and enjoyment, which is quantified as being of a significantly high degree, thereby surpassing conventional thresholds and expectations.

[Article 3: Terms of Vehicle Ownership and Financial Commitments]

3.1 The undersigned hereby asserts exclusive possession and control over a personal motor vehicle, colloquially referred to as “hoopty-hoopty-hoop,” notwithstanding any existing financial encumbrances or obligations pertaining to said vehicle, including but not limited to lease or rental agreements.

3.2 The undersigned reserves the right to prioritize personal satisfaction, well-being, and social interactions above traditional and customary financial responsibilities, explicitly including the payment of housing rent for the current calendrical month.

3.3 The Parties retain the right to engage in personal relationships and social interactions at their discretion, emphasizing a lifestyle of freedom and indefinite continuation.

3.4 Participants are encouraged to partake in a communal verbal expression, specifically the repetition of the phrase “Ray, ray, ray,” as a demonstration of group solidarity, enthusiasm, and celebratory spirit. 3.5 The undersigned are advised to engage in liberal financial expenditure, particularly in light of recent or impending receipt of remuneration or income, colloquially known as “payday.”

3.6 The right of personal identification and nomenclature is hereby preserved, allowing participants to utilize any preferred names or aliases, including but not limited to the moniker “Onika,” with an alternate reference of “Nicki.”

[Supplementary Section B: Reiteration of Dance Floor Engagement Terms]

B.1 The Signatories hereby restate and emphasize their commitment to the aforementioned dance activities, underscoring the critical and potentially final nature of such engagement.

B.2 A renewal of the open invitation for increased participation in dance activities is hereby issued to all parties, with the objective of enhancing the collective experience and fostering an environment of shared enjoyment and social interaction.

[Article 4: Continued Directive on Celestial Aspirations and Elevation Intent]

4.1 The assertions and commitments outlined in Article 2 regarding the design and purpose of spacecraft, including their capability for atmospheric ascension and space travel, are hereby reasserted and emphasized.

4.2 A reiteration of the encouragement for participants to perform the symbolic act of reaching towards the sky is made, symbolizing the continuation of their aeronautical aspirations and the sustained nature of their elevated experiential state.

4.3 The Parties reaffirm their unwavering commitment to these activities, with an emphasis on their perpetual and uninterrupted nature, signifying a continuous desire to maintain and enhance this state of heightened experience.

[Sub-Article 4.1: Final Affirmation of Elevated Status]

4.1.1 In concluding the terms of this agreement, the Parties reiterate and confirm their metaphorical state of elevation in terms of excitement, enjoyment, and collective euphoria, maintaining that such state is at a peak level, far exceeding normal or ordinary experiences.

[Article 5: Ultimate Declaration of Celestial Commitment and Non-Cessation]

5.1 The foundational principle that spacecraft, herein referred to as “starships,” are destined and designed for high-altitude flight is underscored and reiterated.

5.2 Participants are advised and encouraged to perform the symbolic gesture of raising their hands towards the heavens, as an expression of their commitment to these elevated experiences and aspirations.

5.3 An explicit commitment is made to repeat these activities with unwavering enthusiasm and determination, symbolizing the enduring nature of these collective aspirations and the non-negotiable intent to continue these experiences.

[Sub-Article 5.1: Ultimate Altitudinal Declaration]

5.1.1 In the final stipulation of this agreement, the Parties declare that their metaphorical altitude, in terms of collective enthusiasm, excitement, and emotional elevation, is at an unprecedented high, surpassing standard measures and societal norms, thereby sustaining a state of unparalleled exhilaration and communal elation.

I asked ChatGPT to rewrite the lyrics to Getaway Car in legalese.

As it says in the title, I asked ChatGPT to rewrite the lyrics to Taylor Swift’s Getaway Car in legalese. Here’s the first verse and chorus:

[Intro]

In a manifestly assertive negation, it is incontrovertibly stipulated that the origination of outcomes imbued with a propitious disposition is incommensurate and fundamentally antithetical to the operational parameters and designated utility of a mechanized vehicular entity, which has been specifically earmarked and allocated for the facilitation and execution of an expedited egress in scenarios necessitating precipitate departure.

[Verse 1]

The designated chronometric segment under meticulous scrutiny herein is demarcated by an assemblage of circumstances that collectively epitomize an unparalleled zenith in the ambit of societal and personal fortitude, prosperity, and well-being, thereby engendering a juxtaposition of considerable magnitude against a tableau of actions constituting egregious violations of statutory legal provisions, ordinances, and codified regulations, encapsulating a spectrum of moral turpitude and legal infractions. I partook in an act, premeditated in nature, entailing the initiation of a chemical reaction via the deliberate introduction of an incendiary element, an act which precipitated a metaphorical and substantive reconfiguration and upheaval of your mental faculties and perceptual paradigms, notwithstanding the absence of any inimical intent or malevolent foresight inherent in such actions.

It is incumbent upon the discourse to acknowledge and underscore that the actions aforementioned were undertaken devoid of any ill will or malevolent predilection, yet notwithstanding this, your sensory interpretation and cognitive apprehension mechanisms failed in their capacity to accurately construe, interpret, or apprehend the multifarious implications and underlying nuances of these events. The sartorial selections of the period in question were imbued with chromatic attributes reminiscent of traditional mourning, juxtaposed in stark contrast against fabrications and representations characterized by an absence of blemish, taint, or impurity, thereby manifesting a dichotomy in both visual and moral symbolism within the context of the prevailing social and cultural mores.

In an environment delineated by a gradation of chromaticity lacking definitive resolution and clarity, all under the penumbral and subdued emanation of luminescence originating from a light source constituted of a hydrocarbon wax-based material, the setting embodied a confluence of ambiguity and interpretive complexity.

There existed within the sphere of my personal inclinations a prevailing propensity towards the severance and disassociation from the male individual in question, an inclination necessitating the formulation, articulation, and subsequent establishment of a rationale and justification, which would withstand and endure the scrutiny and evaluation of both legal and ethical dimensions, maintaining adherence to established jurisprudential standards and moral doctrines.

[Pre-Chorus]

A symbol, embodying significant gravitas and indicative import, was strategically and deliberately positioned to demarcate and signify the specific geographical and metaphorical point at which the disintegration, dissolution, and unraveling of our interpersonal dynamic and relational paradigm transpired, marking a definitive cessation of previously established relational constructs.

The male party in reference, through a series of deliberate actions and machinations, undertook the intentional adulteration and contamination of the metaphorical wellspring, a conceptual entity representing the essence of truth, authenticity, and veracity, concurrent with my own engagement in a process of self-delusion, a narrative construction in direct opposition and contravention to the objective realities, truths, and factual certainties of the prevailing circumstances and situational context.

From the very inception and embryonic stage of our association, an event symbolically marked and denoted by the partaking and imbibing of an alcoholic beverage deeply entrenched and rooted in historical, cultural, and traditional significance, the trajectory, ultimate denouement, and eventual culmination of our partnership were preordained and foretold to be one inherently devoid of success, fruition, or positive culmination, echoing the sentiments of predetermined futility and inevitability.

The probability, likelihood, and chance of achieving any form of favorable outcome, success, or positive realization in our surreptitious, clandestine, and covert undertakings and endeavors bore a striking, pronounced, and remarkable resemblance to the improbability, unlikelihood, and near impossibility of successfully executing and accomplishing a firearm discharge, an act of ballistic engagement, in a milieu, environment, and setting entirely devoid of visual assistance, aid, or illumination, reflective of an absolute absence of perceptual clarity and visual acuity.

[Chorus]

Your role, position, and function within the narrative construct and unfolding tableau were that of the principal operator, navigator, and director of the automotive apparatus, a mechanized and engineered vehicle specifically, meticulously, and expressly designed, engineered, and assigned for the overarching purpose and objective of executing, facilitating, and effectuating our strategic, premeditated, predetermined, and expedited withdrawal, egress, and departure from a given locality, geographic location, and specific vicinity.

The path, trajectory, course, and direction which we embarked upon, initiated, and commenced, while outwardly presenting, exhibiting, and manifesting an illusion, semblance, and appearance of forward, onward, and progressive motion, movement, and advancement, were, in their intrinsic, inherent, and fundamental essence, nature, and substance, devoid, bereft, and lacking any significant, substantive, or meaningful advancement, progression, or forward movement towards a preconceived, predetermined, envisioned, or anticipated goal, endpoint, objective, or destination.

It is incumbent, obligatory, and behoove upon you to eschew, refrain, and abstain from the adoption, assumption, and portrayal of a facade, guise, or appearance of engineered ignorance, feigned unawareness, or contrived obliviousness in relation to, concerning, and regarding the intricate, multifaceted, and complex enigma, conundrum, and puzzle that encapsulates, defines, and characterizes the complexities, nuances, and intricacies of our shared, mutual, and joint predicament, situation, and circumstance.

I exhort, encourage, and implore you to engage, partake, and immerse in a process of introspective analysis, reflective examination, and contemplative assessment, a process focusing, centering, and concentrating on the specific geographic locale, coordinates, and location at which our initial interpersonal engagement, interaction, and subsequent relational evolution, development, and progression commenced, initiated, and began, thereby marking and signifying the commencement, inception, and initiation of our initial encounter, interaction, and the subsequent series of relational developments, interactions, and engagements that ensued and followed thereafter.

In the process of navigating, maneuvering, and traversing within a vehicular construct, entity, and apparatus explicitly, meticulously, and specifically engineered, designed, and constructed for the primary, fundamental, and overarching purpose and objective of enabling, facilitating, and providing for swift, efficient, unencumbered, and unimpeded relocation, movement, and transition from an immediate, specific, and particular vicinity, locale, and area.

The manifestations, expressions, and physiological responses within, encompassing, and pertaining to the anatomical region, area, and zone encompassing, incorporating, and including your cardiac system, heart, and cardiovascular apparatus bore a remarkable, noteworthy, and striking auditory resemblance, parallel, and similarity to signals, sounds, and auditory cues traditionally, conventionally, and customarily associated with, linked to, and indicative of situations, scenarios, and circumstances of imminent peril, danger, emergency, or exigent and urgent conditions and situations.

The foresight, anticipation, prescience, and forward-looking awareness of my propensity, inclination, tendency, and predisposition towards initiating, instigating, and effectuating a cessation, termination, and discontinuation of our collaborative venture, endeavor, and association should have been readily apparent, discernible, and evident within the bounds, confines, and parameters of reasonable predictability, foreseeability, and anticipatory projection, reflective of a standard of foresight and anticipation consistent with rational, logical, and prudent judgment.

I implore, urge, and beseech you to direct, focus, and orient your intellectual, analytical, cognitive, and contemplative faculties, processes, and capabilities towards a thorough, comprehensive, exhaustive, and extensive evaluation, assessment, and examination of the venue, setting, and location that signified, marked, and denoted the commencement, initiation, and onset of our initial encounter, interaction, and the subsequent series of relational developments, interactions, engagements, and exchanges that ensued and followed in the subsequent temporal progression.

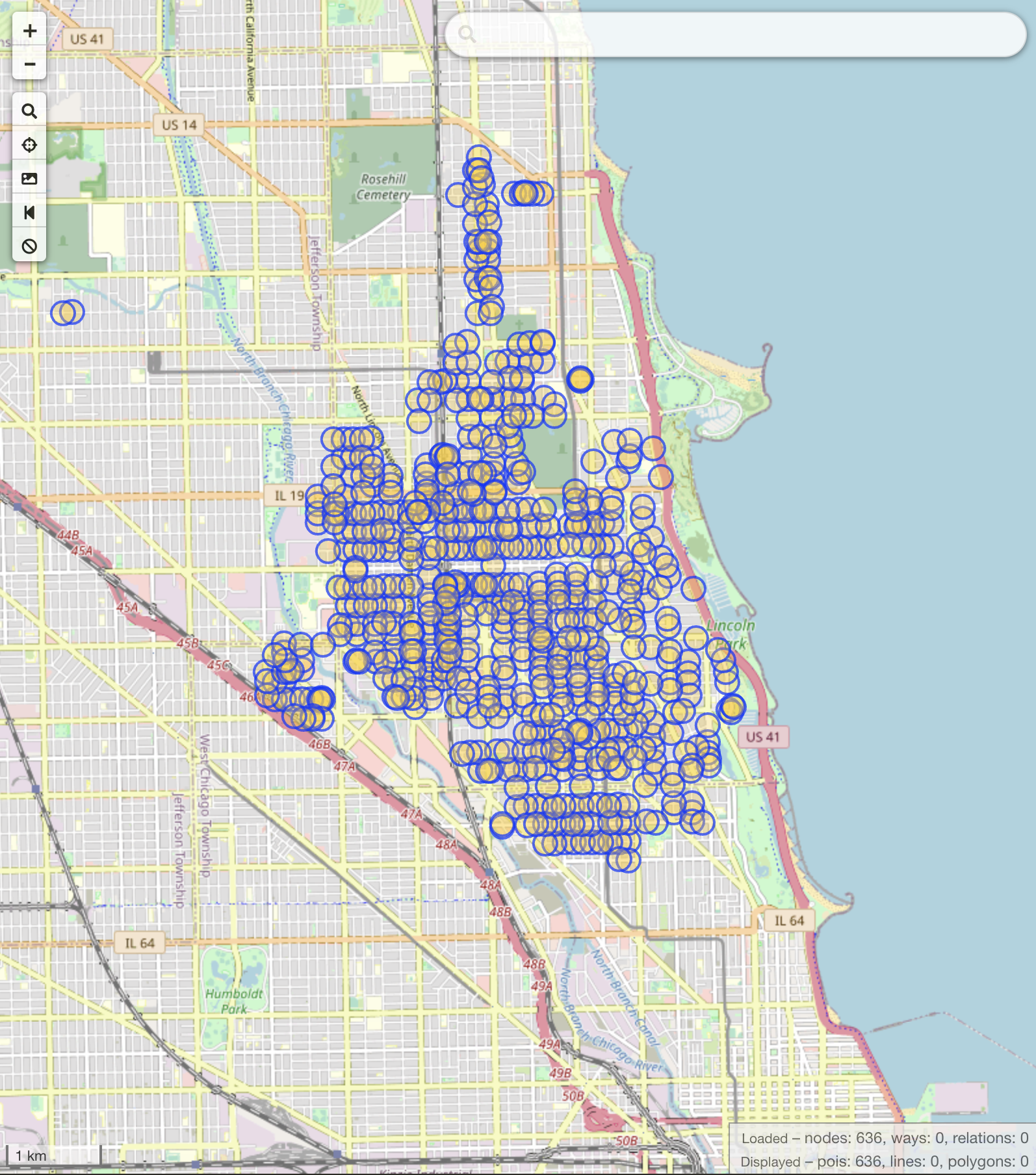

Mapping 636 stop signs on OpenStreetMap

Lately one of my hobbies has been mapping stop signs on OpenStreetMap. The Chicago area has huge gaps in its network of stop signs. This lack of coverage affects mapping and vehicle routing solutions that rely on OSM data, including routing tools for cyclists. Apps like Strava, Ride With GPS, Komoot, and more all rely on OpenStreetMap data to power their routing algorithms. And if the data isn’t up-to-date, the routes can be odd or unexpected.

So I’ve started adding stop signs to Chicago’s street map, 636 of them (so far). I think the goal is to eventually have all the city’s stop signs mapped, and to use that data to power a custom routing engine for bikes in the city. Roads with a higher concentration of stop signs usually feel safer to me. Some stop sign types, like stop=minor need to be avoided as they are particularly dangerous intersections. Hopefully this map data can help folks out and make the community safer.

Third day at the new job, really liking it so far! Feels good to be getting back into a regular 9-5 with some consistency (and a paycheck lol).

Currently reading: Children of Time by Adrian Tchaikovsky 📚

Mapillary Timelapse - East Lakeview

Went out and recorded some footage for Mapillary today. Rode around some side streets in Lakeview that don’t have 360 imagery on them and are pretty old. You can watch the timelapse here.

I’ve been using the new Mapillary uploader that supports the GoPro .360 files for a little while and am pretty impressed. Instead of having individual photos that are taken every 2 seconds on the GoPro, you take a timelapse while biking or a video while driving. Mapillary will then process the video, taking individual frames from it every so often and matching it up with the GPS data.

The advantage of this approach is that it’s a loooot simpler for people recording. Timelapse videos take up much less space than hundreds upon hundreds of photos and impact the battery a lot less. They also offer higher interval recording - the GoPro Max only offers 360 timelapse photos at a 2s interval, while video timelapses can have photos taken every half second. You can also level out the footage after you’ve taken it by exporting to a HEVC MP4 with the GPS data encoded. By far my largest complaint with Mapillary is that they don’t do horizon leveling on photos, which makes for an awful experience for mappers. This export approach fixes that, at the expense of lower quality.

The downside of this approach is the lower quality. The photos produced by it tend to appear more compressed, have lower dynamic range, and don’t look that great in shade or preserve details well. If you don’t upload the raw .360 files, the compression Mapillary uses to serve lower-res segments while zoomed out doesn’t play nice with the compression added to the HEVC MP4, leading to 360 photos that look even messier. But if you do import the raw 360 file, Mapillary doesn’t horizon level things, and it still doesn’t look as good as a regular photo.

I recently bought an Insta360 X3, and I have a GPS module coming for it in the mail soon. The X3 has a photo interval mode and I’m interested to see how well it works as an alternative to the Max. The X3 has horizon leveling built in at the camera level (and it’s fantastic) so I’m hoping the photos made by it will look better.

GoPro Max as a cycling dashcam

I’ve been using the GoPro Max for the past six months as a cycling dashcam, and I think I can now recommend it as a daily driver for all cyclists. The Max is a 360 camera by GoPro that has a variety of mounts and two killer features that make it an ideal fit for recording and storing lots of high-quality 360 video: a) quick capture, and b) auto-upload.

Quick capture is a feature that allows you to press and hold the record button on top of the GoPro and instantly start a video or timelampse. If the camera is off, it’ll turn on and instantly start recording. You can customize what video mode the GoPro will start recording in (quality, 360 or 180, etc.). But this works significantly better than just about any other camera I’ve ever used. Once you set the setting right, you can strap the camera to your helmet, remove the lens covers, and just press and hold the record button to get going. It’s seamless.

The GoPro subscription (about $50 a year) gives you unlimited cloud backup of all of your 360 videos. When you plug the Max into the wall to charge, it will instantly connect to your home wifi network and start uploading content to the cloud. When it’s done, you’ll get a notification in the GoPro app on your phone. GoPro’s subscription gives you unlimited cloud backup of all your videos, which is a huge steal for 360 video. An hour of 360 video on the Max can easily be 5-10GB, so having it all backed up in the cloud for a price this cheap allows you to continue recording tons of 360 video daily while deleting all the old content every so often. In addition to storing the video, GoPro will also automatically export your content to MP4 for you and downsample it. It’ll also stitch the GoPro’s smaller .360 outputs for one video into a single .360 video.

These two features, combined with the cheaper price tag of the Max, allow me to unequivocally recommend this camera as the choice for cycling commuters. It’s easy to switch batteries in and out, the helmet mount works fucking perfectly, and the reframing capabilities are just as good as any other app. This, combined with the lightweight design and the great microphone quality, make it perfect for recording lots and lots of 360 video on your rides to and from work or for leisure.

Thoughts on delivery vehicles in cities

Okay, so my friend Mike made a response to a really dumb car-brained take on Twitter. And as I started replying, I realized I had more complicated thoughts on them, so I decided to write them out here. Also, I’m on Micro.Blog now.

Here’s the tweet he quoted:

The entitlement is crazy here as if there are “Delivery Lanes or designated parking spaces. Yet everybody wants their packages to be delivered in a timely manner. You’re on a bike, just ride around, and let the delivery person DO THEIR JOB.

And here’s his response:

Unpopular opinion. My god do I hate that everybody orders everything online.

We live in a city. Find a store and go to the store. Go outside, it’s good for you.

Online shopping and food delivery apps are so gross. ESPECIALLY cuz we know their employees so taken advantage of

These companies put more dangerous massive heavy trucks and vans on the road. These companies are among the largest repeat offenders of bike lane and crosswalk obstructions.

Fuck online shopping, online shopping created this stupid problem

I have mixed opinions on this. On the one hand, I’m a Chicago cyclist. I’ve had my fair share of close calls with drivers because a delivery driver decided to park their 18-wheelers or FedEx trucks in the bike lane, forcing me out into traffic. On the other hand, I have plenty of friends who are delivery drivers themselves. And on the other other hand, I rely a lot on delivery services to help me function.

First, one of the main reasons why I no longer ride in the bike lane in Chicago is because they are very frequently blocked: sometimes by regular drivers, sometimes by delivery drivers, both equally dangerous. When a bike lane is blocked, I have two choices: I can swerve around the vehicle into traffic, or I can come to an emergency stop. I have to choose between these two decisions in a split second, and both are incredibly risky. When going around the vehicle, I risk being run over by drivers who are completely unaware of my existence as a cyclist (SUVs have atrocious blind spots). When attempting an emergency stop, I risk being run into by cyclists behind me, running into the vehicle, or launching over my handlebars if I pull it off wrong. Neither of these options are safe, so I don’t ride in the bike lane anymore.

So I have a lot of empathy for cyclists angry at delivery drivers for parking in bike lanes, because it risks their lives. Every week in Chicago feels like we’re on a ‘murder of the week’ show as we see a new cyclist or bike commuter dead because a driver parked in the bike lane or a driver wasn’t looking where they were going. And when the bike infrastructure is as shit as it is in Chicago, it feels reasonable for cyclists to be protective of what little we have, and angry over violations of its use.

But at the same time, I have plenty of friends who work for UPS. Working as a delivery driver for UPS is a stressful job. You have to fucking book it constantly because your route is timed. That’s stressful. And due to the lack of proper loading zones in Chicago, and the overabundance of parking, delivery drivers don’t have the time to find a proper parking spot. When you have tens or hundreds of packages to deliver in a single shift, parking once or twice in a bike lane just so you can get back on a fast pace seems like a reasonable tradeoff. And UPS is a unionized workforce! For delivery drivers at FedEx or at Amazon, who are not unionized, the pressure to perform at an unreasonably fast pace is even heavier. So I don’t place a lot of the blame on the workers here.

I also have a hard time blaming people who use delivery. Plenty of people also rely on delivery for good reasons, like disability. I have a hard time going to the grocery store. The two grocery stores closest to me have cramped aisles, awful yellow lighting that hurts my brain, and crowds of loud people constantly needing to push past each other. Every time I need to go to them, I dread going because of sensory issues, and I constantly forget things I need. It takes me twice as long to find shit and I don’t get everything I need to cook.

So I and a lot of other neurodivergent people rely heavily on grocery delivery. I get it once a week or so to keep my kitchen stocked and help make cooking easier. I just do not have the energy to go to the store regularly except for quick visits. And that to me is an accommodation because my brain just does not work like other people’s. If I spend too much of my energy trying to cook and get groceries, I end up exhausted and won’t be able to take care of myself in other ways. So over the last few months, I’ve begun to rely increasingly on parcel + grocery delivery to save me trips to stores that overwhelm me sensory-wise (and also risk my life as a cyclist).

So I also don’t blame people who use delivery services. I think delivery services are good and necessary for a city to function well. They’re one of the many conveniences of living in a denser area: because of the density, it’s cheaper to do local delivery than it would be in a suburban or rural place. And it helps people like me who kinda need it in order to function for my job or just for my own mental health.

So who to blame then? Auto manufacturers. Private vehicles do not belong in cities, period. All of the roadways that delivery drivers and service vehicles could rely on to get their jobs done are instead used inefficiently by car commuters. Instead of having loading zones in front of stores, we have miles and miles of parking, most of which goes unused. We have untrained drivers who are really bad at it and shouldn’t be behind a wheel, but they drive to work anyway because it’s ‘more convenient’ and ‘there isn’t any alternative’. After years of lobbying local governments and spreading auto propaganda, auto manufacturers and oil companies forced us to become dependent on their inefficient, wasteful motorized carriages to the point where we can’t imagine any alternative way to navigate a city.

Get rid of auto companies and cars, and you have the tools to build an enjoyable, thriving city. But any amount of half-measures or trying to be nice to private vehicle owners will put you exactly where you are now.

What is the void keyword in TypeScript?

One of the more confusing types in the TypeScript universe is the void type. The most common place it’s used is as the return type for a callback function. For example, the type of the callback you pass to the Array forEach function is this:

type CallbackFn<T> =

(value: T, index: number, array: readonly T[]) => void;

The forEach callback accepts three arguments: the current value (T), the current index, and the array (readonly T[]). Its return type is the void type.

Most people think that the void type means ‘returns undefined’, and that void and undefined are interchangeable. For example, TypeScript accepts both of these callback functions as valid:

const logNumbersVoid = (num: number): void => {

console.log(num);

return undefined;

}

const logNumbersUndefined = (num: number): undefined => {

console.log(num);

return undefined;

}

// TypeScript doesn't complain about either of these.

[1, 2, 3].forEach(logNumbersVoid);

[1, 2, 3].forEach(logNumbersUndefined);

These two functions (logNumbersVoid and logNumbersUndefined) are the same, except for their return type. Both accept a number as their parameter, log the number, and return undefined. The first function’s return type is void, and the second one is undefined.

TypeScript allows us to use both of these as the callback to the forEach function. So, it seems like void and undefined are doing the same thing.

However, there are some cases where void allows some things that undefined does not:

const logNumbersVoid = (num: number): void {

console.log(num);

// Note that we're returning `num` in both functions.

return num;

}

const logNumbersUndefined = (num: number): undefined {

console.log(num);

// TypeScript complains about this but not the other one???

return num;

}

Here, we change both functions to return num instead of undefined. TypeScript complains about the return statement in logNumbersUndefined, but doesn’t complain about the return from the void function.

What’s going on here? Why are we allowed to return a number from a void function but not from an undefined function? Let’s dig deeper.

Where does void come from?

Several constructs in TypeScript have similarly named constructs in JavaScript. For example, TypeScript’s typeof operator comes from the typeof operator in JavaScript, working similarly to it in type definitions. It’s useful to understand the JavaScript version of these TypeScript constructs. Knowing the behavior in JavaScript can help us predict how they’ll behave in TypeScript.

Just like typeof, TypeScript’s void type has a counterpart in JavaScript: the void keyword.

The void keyword in JavaScript is a keyword that can be put before any expression (something evaluating to a value). JavaScript will evaluate the expression and then return the value undefined for the entire expression. So in the example below, “It returned undefined!” would be logged to the console:

if (void "helloWorld" === undefined) {

console.log("It returned undefined!");

}

void works similarly to typeof in that it evaluates the expression to the right of it. However, void throws away the result of the expression. In this way, void sort of acts like a trash can: the value of any expression you give it will not be accessible again. Hold on to that analogy for a minute.

Use of void

It might seem like the void keyword doesn’t have much of a use case now, and you’d be right in thinking that. But before ES5 JavaScript, it had an important use case: getting the value undefined.

In JavaScript, there are two versions of undefined: the value and the variable. For whatever goddamn reason, undefined is actually a global variable in JavaScript, not a reserved word. By default, this variable points to the value undefined. Tricky, I know.

Before the ES5 standard, any script could modify the contents of the undefined variable. Running something like window.undefined = "HAHA FUCK YOU" could potentially screw up a large part of most working programs (e.g., conditions like variableName === undefined would return false).

Because of this, many JavaScript developers would use the expression void 0 to obtain the undefined value. Contrary to the undefined variable, void is a reserved word that cannot be modified or changed. This meant that variableName === void 0 would always return true if variableName was undefined, even if someone re-assigned the undefined variable.

The ES5 standard changed undefined so that it was read-only, so thankfully these kinds of bugs / exploits no longer exist. The resolution of this issue removed one of the main use cases for void. As a result, most JS programmers don’t know about it.

void in TypeScript

The TypeScript Handbook describes void like this(https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/2/functions.html#void):

voidrepresents the return value of functions which don’t return a value. It’s the inferred type any time a function doesn’t have any return statements, or doesn’t return any explicit value from thosereturnstatements.

So void is a type used when our functions don’t have any return value. If we don’t have any return statements in the function, TypeScript will automatically assume that our function returns void. This explains the typing of the Array.prototype.forEach callback: forEach isn’t concerned with the result of the callback, only the parameters it needs to pass to it.

If void is inferred by TypeScript only when nothing is returned from the function, why could we return undefined in the example at the beginning of the post? The handbook goes on:

In JavaScript, a function that doesn’t return any value will implicitly return the value undefined. However,

voidandundefinedare not the same thing in TypeScript.

In JavaScript, any function that doesn’t return a value automatically returns undefined. As consumers of a function, we have no way to tell whether the return of undefined was explicit (return undefined;) or implicit (no return statement). Therefore, TypeScript allows us to return undefined from a void function. As consumers of that function, we can’t tell the difference between the two.

But hold on a second, why does the handbook say that void and undefined are different? Scrolling down to the bottom of the page(https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/2/functions.html#return-type-void), we read this:

Contextual typing with a return type of void does not force functions to not return something. Another way to say this is a contextual function type with a

voidreturn type (type vf = () => void), when implemented, can return any other value, but it will be ignored.

This is saying that when we have an explicit return type of void (like in both of our functions before), we can return any type from our function. In other words, any type is assignable to void when we’re returning from a function.

This is not the case with a function with a return type of undefined: TypeScript will force us to either return nothing, or explicitly return undefined. Contrary to this, void doesn’t care. We can return implicit undefined, explicit undefined, or any explicit value we want.

Remember what we said about JavaScript’s void being a trash can? TypeScript’s void is the same way, but as a type. Once you assign something to void, TypeScript won’t let you use it again. You can put stuff into it, but you can’t get stuff back out. Once you tell TypeScript that something is void, it throws out whatever type it was before and starts treating it like nothing. It’s a trash can.

So that’s how void works in TypeScript.